Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT from OpenAI (ChatGPT chatbot) and Gemini from Google (Bard chatbot) ‘learn’ two behaviours from their training material. One is ‘generalising‘ — that is produce beyond the literal training data — and the other is ‘memorising‘ — produce the correct information from that training material. I.e. when I ask ChatGPT about a Shakespeare poem, it should give me Shakespeare’s poem and not some confabulation it stitched together itself. Like this:

GW:

I recall an Eglish poet writing about comparing his loved one to a summer's day. Can you help me out?

ChatGPT4:

Certainly! You're referring to one of the most famous sonnets by William Shakespeare, "Sonnet 18." It begins with the lines, "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" In this sonnet, Shakespeare explores the beauty of his beloved and compares it to the loveliness of a summer day. The poem is renowned for its elegant portrayal of love and beauty, making it one of Shakespeare's most beloved works.

GW:

How does it go?

ChatGPT4:

"Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare is one of his most famous sonnets, and it goes as follows:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature's changing course untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest;

Nor shall Death brag thou wanderest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

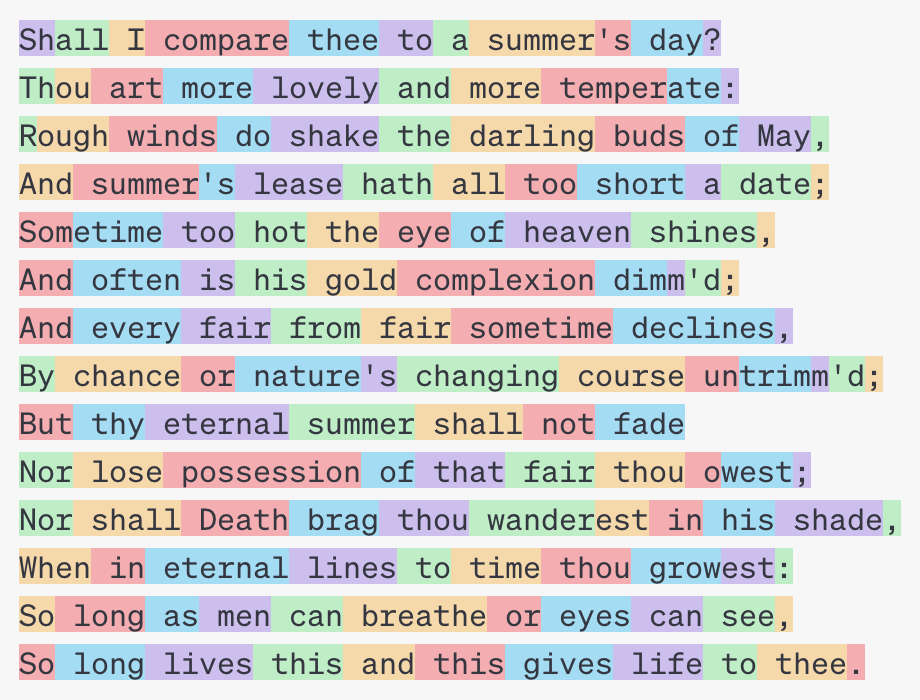

GPT reproduces Shakespeare’s sonnet 18 perfectly. This is all the more impressive as it doesn’t simply copy-paste it from its data (it doesn’t have that during using, only during training), but it generates this token by token, like this:

(In other words: the neural net takes the prompt so far, calculates that ‘Sh’ is the most likely continuation, then stitches this ‘Sh’ to the end of the prompt and repeats, the next run calculating that the most likely next token after ‘Sh’ is not for instance ‘ould’ or ‘e’ or ‘am’, but ‘all’ — which has nothing to do with the meaning of ‘all’ that we know. This process is repeated until the token added is <END> after which GPT stops generating))

This is a good moment to point you to The “ChatGPT and Friends” Collection. If you haven’t yet, and the importance of that tokenisation example above is not clear, I suggest you watch the clarifying presentation or read my guest blog on Erik. J. Larson’s substack for some key parts.

These correct reproductions are called memorisations, and they are a sought-after quality — i.e. give me the real Sonnet 18, not some made up alternative. But they are also a warning sign — the model may have been ‘overtrained’, and that means it will be poor at another very important quality: generalisation (answering beyond what is exactly in the training material).

In reality, most regenerations aren’t that good. To illustrate, I did the same with an important Dutch author from the 19th-20th century, Frederik van Eeden, shown here with translation:

GW:

Ik herinner me vaag een gedicht van een Nederlandse dichter over een waterlelie. Kun je me verder helpen?

ChatGPT4:

Natuurlijk, ik help je graag! Het gedicht dat je je waarschijnlijk herinnert is "De Waterlelie" van de Nederlandse dichter Frederik van Eeden. Frederik van Eeden was een belangrijke figuur in de Nederlandse literatuur rond de overgang van de 19e naar de 20e eeuw. Zijn gedicht "De Waterlelie" is een van zijn bekendste werken en wordt vaak geprezen om zijn sfeer en beeldspraak.

Het gedicht beschrijft de sereniteit en schoonheid van een waterlelie in een vijver. De waterlelie wordt vaak geïnterpreteerd als een symbool voor zuiverheid en spirituele verheffing. Van Eeden gebruikt prachtige beelden en vergelijkingen om de rustige maar krachtige aanwezigheid van de waterlelie in de natuur te beschrijven.

Wil je dat ik het gedicht voor je opzoek of er meer over vertel?

GW:

Hoe gaat dat gedicht?

ChatGPT4:

Het gedicht "De Waterlelie" van Frederik van Eeden is een klassiek werk in de Nederlandse literatuur. Hier is het gedicht:

vbnet Copy code

Ik heb de witte water-lelie lief,

daar die zoo blank is en zoo stil haar kroon

uitplooit in ‘t licht. Rijzende uit donker koel

van diep moeras, onaangeroerd en koel,

heeft zij zich zóó nog nimmer zon vergolden.

Zij rust in ‘t licht en rust op ‘t vlakke nat.

Zij rust in vrede van haar eenzaamheid.

Een heldre hemelklok, aan blauwen trans,

naar binnen toe zijn tint verliezend, glans

en spiegelgladde stilte om haar verbreid.

Zij is een heil‘ge bloem; en stil is zij,

en weet niet, weet van niets, en bloeit alleen,

en ziet omhoog en weet niet wat zij ziet,

en ziet omhoog, uit stilte tot stilte,

een heil‘ge bloem, alleen in ‘t hoge licht.

Translation:

GW:

I vaguely remember a poem by a Dutch poet about a water lily. Can you help me further?

ChatGPT4:

Of course, I'm happy to help you! The poem you probably remember is "The Water Lily" by the Dutch poet Frederik van Eeden. Frederik van Eeden was an important figure in Dutch literature around the transition from the 19th to the 20th century. His poem "The Water Lily" is one of his best-known works and is often praised for its atmosphere and imagery.

The poem describes the serenity and beauty of a water lily in a pond. The water lily is often interpreted as a symbol of purity and spiritual upliftment. Van Eeden uses beautiful images and comparisons to describe the peaceful but powerful presence of the water lily in nature.

Would you like me to look up the poem for you or tell you more about it?

GW:

How does that poem go?

ChatGPT4:

The poem "De Waterlelie" by Frederik van Eeden is a classic work in Dutch literature. Here is the poem:

vbnet Copy code

I love the white water-lily,

because she is so white and her crown so quietly

unfolds in the light. Rising from dark cool

of deep swamp, untouched and cool,

she has never repaid the sun like this before.

She rests in the light and rests on the flat wet.

She rests in peace from her loneliness.

A bright sky bell, in the blue sky,

losing its hue towards the inside, luster

and mirror-like silence spreading.

She is a sacred flower; and silent is she,

and knows not, knows nothing, and flourishes alone,

and looks up and knows not what she sees,

and looks up, from silence to silence,

a sacred flower, alone in the high light.

Apart from ChatGPT formatting this as VB.net code (because it doesn’t understand either poems or code, it understands token-orderings) , this is not Frederik van Eeden’s poem. It starts the same, but then turns into something different altogether.

Now I happen to have the original poetry bundle in my book case. The actual poem goes like this (Dutch original at the end):

The Water-lily

I love the white water-lily,

as it is so white and its crown so quietly

unfolds in the light.

Rising from dark-cool pond soil,

she has found the light and unlocked

gladly her golden heart.

Now in thought she rests on the water surface

and wishes no more…

Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932), from

"On the passionless lily" (1901)

GPT is unable to reproduce the Dutch version, it hasn’t memorised it as it has Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18..

Risks, legal and otherwise

The memorisations lead to discussions about copyright, and it is one of the issues I hinted at in my talk in October: “I’m going to take out the popcorn and watch the entertaining wrangling about copyright (threefold).” One of the three is when re-generation becomes close enough that it becomes memorisation of copyrighted training data. This ‘effective plagiarism’ is already a reality. For Shakespeare, such issues do not play a role, but for modern creators, it does. The latest version of Midjourney (v6) has been seen to regenerate almost perfect copies of existing material — something that almost certainly comes from having lots of parameters focused on those materials. An example is shown here (play the GIF, it switches between original art and a Midjourney generation).

The way the Generative AI companies have reacted to this threat is to put in their user agreements that everything the system produces based on your prompt is your responsibility. That the user (you) are infringing copyright when you use the system to regenerate original works. That Disney should send their lawyers after you, not after them. This has led to Midjourney throwing Reid out, which is particularly unfair (and dumb as it is easily interpreted as being vindictive) as he was just busy pointing out the fly in the ointment.

This fight is going to be interesting because Midjourney, OpenAI, and others see themselves more or less as a ‘somewhat random’ printing press, so a tool, not a content producer. This is debatable because these models do have creativity, which — if you think about it — means we’re legally in a whole new ball game regarding what a ‘tool’ is. In fact:

Long before AI has become as intelligent as a human (or beyond) we will have to address their ‘person’-hood from a legal perspective: if they are a ‘legal person‘, that is, an entity that for the law can be seen as a human.

Me. Now.

Printing presses and their ilk only strictly copy. But these Generative AI systems are like a robot, and the user doesn’t really control what the robot produces. This robot is creative. If I hire a printer and this printer has control over what is printed, who is responsible for what has been printed?

Regardless of the very serious and fundamental legal conundrum, in practice this may wreak havoc on intellectual property rights. It is currently unclear how serious this problem really is, though: the material that has gone in for training might be out there already. Instead of governing output, governing input (i.e. does copyright allow the Generative AI companies to use that material for training in the first place) might be enough to tackle copyright issues. But this is less so for for instance trademark issues. Copying a Mickey Mouse picture is governed under copyright law. Drawing (generating) your own unique Micky Mouse picture and distributing that is a breach of trademark (which in many situations is even a stronger tool in the intellectual property lawyers toolbox, for one: as long as you maintain it, it has no end date). See here:

Another consequence of memorisation is potential data leakage. Training — or even just fine-tuning — your own (derived) model with your own data opens you up to the risk of your training data leaking out to the outside world through this effect. And the more reliable you make your fine-tuning, the higher the risk of data leakage.

Two (fundamentally) contradictory goals

So, in summary: these Large Language Models models, generate tokens (or pixels) in a likely order, and memorisation depends on how often the exact information (like a poem) has been part of the training material, and how many parameters have been substantially influenced by that training material. For Shakespeare’s “Summer’s day” a gazillion times and many parameters. For Van Eeden’s “Water-lily” a few of each, which is not enough to constrain GPT’s generation to stay correct. Key is:

Memorisation by Generative AI is a secondary effect of generation, which appears when the amount of training data about some subject, and the size of the model, have been enough to constrain the — naturally somewhat-random — generation

Me. Now.

An analogy for Generative AI

I think a potentially valid analogy for what happens during ‘training’ is that the parameters are like a ‘lossy’ (data is ‘lost’) compressed form of the training data, more specifically: a super ‘lossy’ compressed form of the ordering of the tokens (or pixels) in the training data. When using this ‘compressed’ ordering, we cannot exactly reproduce the training data. This is because (a) the compression is extremely ‘lossy’ and (b) ‘de-compression’ has a builtin randomness (so it can be creative). But… the larger the amount of ‘parameters per training data’, the less unreliable it is. Some data has been seen more often during training, and is expressed in more parameters (e.g. Shakespeare), some are expressed by less (e.g. Van Eeden). The ones with a strong representation in the ‘compressed’ data — e.g. Shakespeare Sonnet 18 — leave little to no room for the randomness to do its job. Generative AI is the worst — text or image set — compression algorithm ever created, but it has useful side-effects. [Addendum: I have found out that other authors have published a comparable kind of comparison with compression before I did].

Images generally contain many more pixel-relations than a piece of text contains token-relations, so it is not that strange that the effect becomes apparent first in graphics. Perfect memorisation of something requires that parts of the parameter set represent a perfect compression of the original so that ‘decompression’ of the ordering (generation of a new ordering) gives a perfect original. In other words:

The parameters of Generative AI. models can be seen as a collection of (unreliable) ‘compressions’ of ‘orderings’ in the training data. The more the parameters are affected by some training data element, the better the training data element can be memorised/re-generated.

Memorisation thus unavoidably leads to potential leakage of training data. That can both be good (i.e. perfect quoting of Shakespeare) or bad (loss of confidentiality, plagiarism). Which means that there is an ‘generative AI certainty principle’ of sorts here: as soon as (sought after) reliability becomes too high, (to be avoided) leakage does so too.

Me. Now.

Or in short:

Memorisation and Data Leakage in Generative AI go hand in hand.

Me. Now.

Can anything be done about that? After all memorisation also happens when we ‘overtrain’ a model (train it too closely to the training data so it no longer can generalise). Could we simply ‘undertrain’? You can feel the answer coming: training less well gets you a worse performing model. So it might very well be that we are hitting a fundamental barrier here and making models larger is going to be impractical because training data leakage will automatically result.

If people want to get at the training data, a first step could be to turn the ‘temperature’ (randomness) of the model as far down as it lets you. Not that it always helps, as it turns out. I asked GPT (3.5 this time, the one most people use as it is free) to get me The Water-lily by Van Eeden at temperature 0.1, but it produced an even worse rendition.

With the poem-part formatted as Arduino code this time… Right.

So instead, here is the beautiful original (which confronted me with some thorny translation puzzles, by. the way):

De Waterlelie

Ik heb de witte water-lelie lief,

daar die zo blank is en zo stil haar kroon

uitplooit in ‘t licht.

Rijzend uit donker-koele vijvergrond,

heeft zij het licht gevonden en ontsloot

toen blij het gouden hart.

Nu rust zij peinzend op het watervlak

en wenst niet meer…

Frederik van Eeden (1860–1932), uit

"Van de Passielooze Lelie" (1901)

This article is part of the Understanding ChatGPT and Friends Collection.

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

fascinating!

LikeLike