TL;DR

If you just want to have the short conclusion on ‘reasoning models’, such as OpenAI’s GPT4-o3, skip to the end.

The longer read gets you the basics of LLMs and where they can scale and some of the efficiency tricks employed (like the fragmentation through ‘Mix of Experts’ approach) to try to fight the inevitable scaling problem. A lot of ‘engineering the hell around a fundametally limited approach’ (i.e. token statistics) has been going on. The ‘reasoning models’ add a (thick) layer of ‘indirection’, but that isn’t reasoning. A dimension has been added, but nothing fundamental really has changed. We’re still approximating, not reasoning. And what is worse, these indirections are ‘narrow’ and pretty inefficient. An ARC-AGI-1 task a human does for $5 on average may currently cost GPT4-o3 $3000 on average — run time, not training time — if we follow the numbers from o3’s human-level performance on ARC-AGI-1-PUB (they may be able to tinker this downward of course, but, frankly, we don’t know if that will be the case).

I do not know much about the actual internals of models like GPT. We know — since Vaswani (2017), yes it already has been 8 years… — the basics, of course:

LLMs do not work on words, it only seems that way to humans. They work with tokens. If you do not really know what a ‘token’ is, it is not always a word (or anything that you would recognise as a linguistic element). A token is mostly a fragment of characters of variable length that enable you to glue them together to create all text. LLMs work with a limited set, GPT3 had a fifty thousand token ‘dictionary’ (again a somewhat misleading term as for humans that means ‘meaningful words’). Token dictionaries may be 100k or 200k in size. Watch this video or read this summary if you want the whole story. Or read OpenAI’s own short explanation and play with the tokeniser there. Confusing tokens with words misleads a lot of people.

Some tokens represent entire words, but if the word is not available as a token it is stitched together as a sequence of multiple tokens. For instance, in GPT3, the word ‘paucity’ was made up of three tokens: paucity, in GPT3.5 and GPT4 it is made up of three tokens as well, but differently: paucity, but GPT-4o goes back to paucity. Grok-1 has paucity as a single token: paucity.

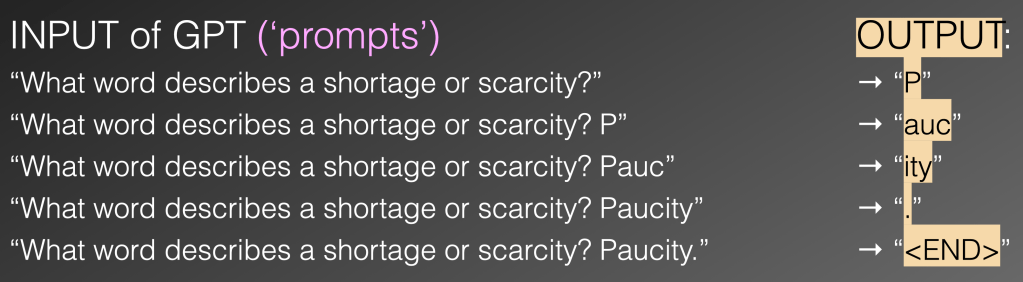

What the model does is break the initial prompt (your input) into tokens and then repeatedly use whatever has come before (both your initial prompt and what it has added to that itself) and produce a new token. So: every newly generated token is added to what is already there until the model signals it is done by providing an ‘end’ token. From my initial EABPM talk in 2023:

This mechanism is called autoregression. So, what these models do is not calculate the best next word, they calculate the next — from a human’s perspective meaningless — ‘best’ next token. ‘Best’ here is ‘randomly selecting from a set of likely best next tokens’. In the example above: after having produced the p token, the ity token gets a low likelihood score (‘pity’ is a valid word, sure, but the token isn’t statistically very likely given what has come before), and most others out of the tens of thousands possible tokens, like the the x of if token even lower (strings like ‘px’ or ‘pif’ don’t happen much in the training material, especially not in this context of other tokens that have gone before).

By increasing the randomness (you can, see my talk — from 2023 but fundamentally still valid) you can get more creative output but also more gibberish.

Basically, a good short definition of an LLM is:

LLMs understand statistical relations between tokens (not per se words) and with that they can approximate the result of real understanding to a certain degree (which sometimes can be amazingly high, and sometimes frustratingly low). LLMs are generally embedded in a complex landscape of other systems that in part mask this from being all-too-visible.

Some of those that think LLMs are a step towards true Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) are convinced that this approximation — if the mechanism is scaled up enough — becomes indistinguishable from real intelligence. Specifically, they think that even logical reasoning — a main weak point of the LLMs as logic runs at the semantic level while tokens are meaningless from a human perspective and run below even the grammar level — will be possible. The thought sometimes in part simply is: we humans can do logic and we too employ neural nets, so it must be possible. (This is not the first time, when AI really started in the late 1950s, it was thought that since neurons ‘fire’ they are ‘digital’ on/off signals. This is false, neurons are very analog and the current ‘neural nets’ tend to be built on that perspective).

But in practice LLMs doing logic is like trying to logic based on the ink distribution of a printed logical argument. Here is an example from my 2023 EABPM talk where you see how token generation has a hard time being logical:

These simple examples are now harder to generate as much development has gone into approximating better and hiding the token-generation game inside a complex web of systems. But fundamentally, they are still there.

Others think that scaling is not enough and something extra is required, often this suggestion takes the form that we need ‘neurosymbolic’ systems, where neural nets such as LLMs are integrated with systems that employ ‘symbolic logic’, i.e. the logic we employ when we for instance deduce that if A is larger than B an d B is larger than C, then A is larger than C. People think this because this kind of logic is extremely hard to do through the approximation of LLMs.

Most people intuitively agree that we may call any mechanism that generates output that we find indistinguishable from what known (human) intelligence can generate simply ‘intelligence’. The Turing Test is an example to decide along those lines (but it fails to test this because it turns out that human intelligence is quite easily fooled). I have been saying this on several occasions: the most interesting thing we are going to learn during this part of the Digital Revolution is probably about our own intelligence (and its strengths and above all weaknesses).

The essential calculation that happens for each token that gets selected as next token

At its core, a LLM calculates one ‘next token’ at a time. It does that by calculating a sort of ‘fitness’ score for all possible tokens. These ‘possible tokens’ make up the ‘token dictionary’. So, for a token dictionary of size 50k, the model calculates 50k times (for each possible token) how good its score is as ‘next token’. This produces a set of ‘best tokens’ of which one is selected with some randomness. That randomness is what makes the LLMs creative. The more randomness you allow (this is called the ‘temperature’) the more creative the model becomes. But the model makers limit this, because if you set the temperature too high, it fails to approximate good grammar. You can see an example in my original talk. They limit this temperature for a reason: regardless of the meaning of what the model puts out, if it fails at basic grammar it becomes far less convincing for us humans. (We can produce good meaning with bad grammar, but the LLMs probably cannot — I never tried).

One of the potential tokens that can be generated is the <END> token, which signals ‘stop generating’.

Note: what people tend to call ‘hallucinations’ aren’t errors at all. They are the ‘perfect’ outcome of the above process and as calculated they are a best generation the model could do. The model approximates what the result of understanding would have been without having any understanding itself. It doesn’t know what a good reply is, it knows what a good next token is, and there is a fundamental difference. It produces good ‘best next tokens’, but these may create a ‘hallucination’. Much work has gone into minimising this effect, but as it is fundamental to the architecture it is probably impossible to get fully rid of it (though at the expense of much processing power you can minimise this but only for a certain type of inference, see ‘reasoning models’ below).

Scale factors of ChatGPT and Friends

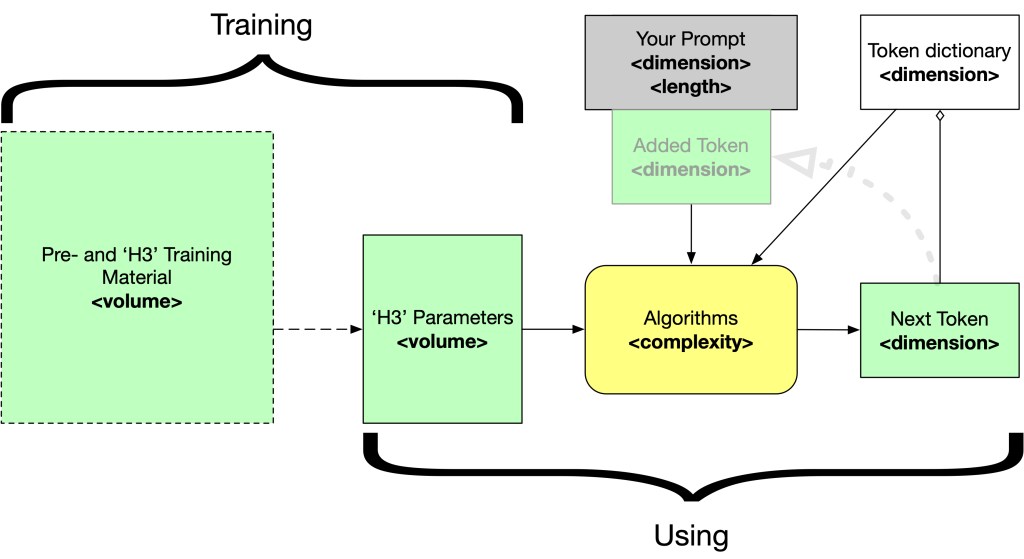

With the usual digression out of the way and before we discuss what the ‘reasoning models’ do and what that means, let’s set the stage. Let’s start with a high level look at a Large Language Models. We go step by step into an overview of the elements and how they can scale. This is the absolute basic idea of an LLM architecture in a diagram:

The green and grey elements in the diagram are data, the yellow element is behaviour. H3 stands for “Helpful, Honest, Harmless”. The reality these days is much more complex, but as a basic mechanism, this works. The key elements that can scale are:

- The complexity of the model. The transformer works not on words — as is often sloppily explained — but on vectors (sets of numbers) that represent tokens. Each token is represented by a vector, the size of which (say a set of 12,000 values for GPT3) is one dimension and the number of different tokens (say, 50,000 for GPT3) is another dimension.

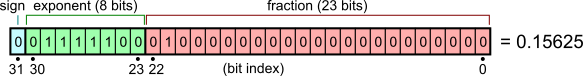

- The volume (not the number) of parameters. Training an LLM ends into a large set of bits that store a fuzzy set of all the different patterns of tokens of the training that training has encountered. The number of parameters comes from the complexity of the model (e.g. layers, etc.), their size depend on the precision of the calculations where they are employed. There has been a development of moving towards ‘more but less precise’ parameters, in part because that is more efficient. It does mean the algorithms have become ‘larger’. So, smaller parameters but more statistical-algorithm. Even simple measures such as ‘number of parameters’ that has often been mentioned is foggy. After all, there is quite a difference between a 32-bit ‘floating point number’ (

float32) or — what Gemini is (partly) using — a simple 8 bit value (8bit). For now, the best measure to compare model sizes may be the parameter volume (in bytes) in combination with number of parameters, the latter a measure for algorithm size.

What also has happened is that a single set of parameters hides multiple separate approximation approaches (the ‘mix of experts’ approach). Such optimisations may make models more efficient, by for instance at some point deciding to not use several of these experts anymore. DeepSeek is a model that does that for instance.

A Digression on Precision (skip if you’re not that interested in these technical details)

Floating point numbers in digital computers, by the way, are not really floating point — or ‘real’ — numbers. They are a collection of three integers (whole numbers). For instance, float32 is 32 bits (4 bytes):

How this works in detail you can read here, but you can easily see that 32 bits can only represent two to the power of 32 different values. That is a grand total of 4294967296 values, which seems large enough, but there are infinite real numbers. Even worse, there are infinite real numbers between 0 and 1. Even worse, there are infinite real numbers between 0.000000001 and 0.000000002. You get the picture. So, when you think about it, such digital representations only can represent a very small fraction (infinitesimally small, even) of all possible real values. There are many gaps in these representations (it’s more or less all gaps) and that may lead to unexpected effects. There is a gap around zero and the larger the numbers become the gaps become large too.

What may surprise you: it is impossible to exactly represent the value 0.1 in a standard digital floating point format.

Wait…. What?

- The volume (and quality) of the Training Material. This must be multiplied by how often this training material is used during training. Here too are some ‘engineering the hell out of it‘ gains: like having models piggybacking their training on other models (again something DeepSeek has done)

- The size of the token dictionary. How many possible tokens there are. GPT3 worked with around 50k. The latest models from OpenAI have a token dictionary of around 200k. The more potential tokens there are, the more fine-grained statistical relations between them are in play.

When we train the model, trillions of ‘tokens’ (how text is represented in these models — not in a way we humans do by the way, see elsewhere in this series) are turned into billions of (bytes of) parameters. In a way, this can be seen as a form of compression of the training material, but not literally. You cannot decompress it to get the training data, but you can generate new material based on the statistical relations between tokens in the training material. If the parameters represent the training material exceptionally well, you can get memorisation (or data leakage — these are the same) of the training material.

When we use the model, the training material is not available, only the parameters and the input are. That input, starting with your ‘prompt’, is the context for generating the next plausible token. Many tokens may be plausible at any point, and with somewhat of a throw of the dice, one is chosen. This generated token is then added to your existing context (your prompt and everything already generated so far), after which the procedure repeats until the next plausible token is an <END> token, which signals that generation should end, as was shown above. This was the situation when ChatGPT hit the world and blew everyone away.

In essence, this basic mechanism has remained the same and so have the limitations of approximating the results of understanding without actually understanding. But OpenAI, Google, and others have been engineering like crazy to improve on the often poor (but still convincing) results.

The technical improvements beyond 2019 GPT3

I am not privy to what goes inside OpenAI, Google, etc., but from what I know of LLMs and what we can see, I can make some educated guesses. I am presenting a few here that are (almost certainly) fact. Warning: I am somewhat assuming that you have read/watched my earlier explanations so words like ‘context’ are understood in their LLM-meaning, not the general meaning. You can glance over them, but if I lose you, the necessary background is elsewhere in my writing and presentations.

1. Context size (via the ‘turbo’ models to the large context sizes of today)

The size of the context — how much of what has gone before do you still use when selecting the next token — is one of the first sizes that have gone up. The OpenAI models with a larger context window were originally called ‘turbo’ models. These were more expensive to run as they required much more GPU memory (the KV-cache) during the production of every next token. I do not know what they exactly did of course, but it seems to me that they must have implemented a way to compress this in some sort of storage where not all values are saved, but a fixed set that doesn’t grow as the context grows that is changed after every new token has been added. To me this smells like a solution that effectively passes on a gigantic ‘state’, not unlike the Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) from the Recurring Neural Networks (RNNs) that gave birth to the Transformer architecture (Vaswani’s Attention [to context GW] is all you need). There LSTM was a huge bottleneck for model growth during training, but during generation this should not be a problem. This state may either come from a simple but inspired trick (like the transformer architecture itself), or it may even be driven by some neural net that is trained as well to create the optimal state. Both, I can imagine. Which one? I do not know. But context size has seized to be the GPU memory bottleneck that it originally was.

2. A bigger token dictionary

This is a small one, but increases the granularity of available tokens for next token and with that the number of potentially tokens to check at each round. From a token dictionary of 50k tokens to a token dictionary of 200k tokens meant that for each step, 4 times as many calculations had to be made. We’ll get to the interrelations of the various dimensions and sizes below.

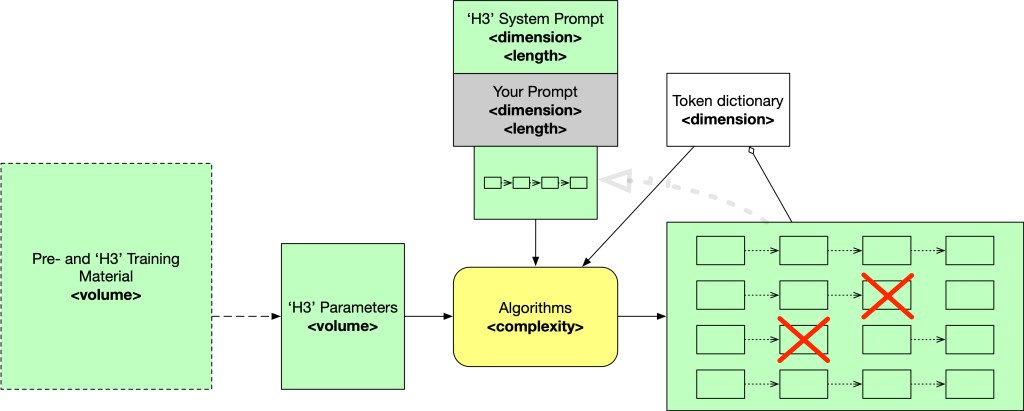

3. Parallel/multi-threaded autoregression

Generating means calculating a set of potential ‘best next tokens’, randomly selecting one of these ‘best next tokens’, adding this token to what has been put in and generated so far and repeating that until that <END> token is generated. One of the improvements has been to do several different generations in parallel. If you have multiple generations, you can compare them over a longer stretch. One regression may come up with an overall higher average fitness score for all its tokens so far, even if maybe the first of that stretch has a slightly lower fitness. And if you delay outputting them until all threads have at that position the same token, or you prune those threads that get into ‘low fitness score sets’ you can give your generation a kind of useful memory. Of course, every extra parallel thread increases the number of calculations that are done. In a picture (with for completeness the ‘system prompt’ added — and reality will be different than the simple picture here)

It is not essential to understand how they calculate ‘token thread’ fitness on top of ‘token fitness’. There are two ways this may have been implemented. At token level, which is simple (just have a formula using the token fitness values). But as this article describes it, it is an extension of Chain of Thought, the approach pioneered in prompt engineering to ask the model to go ‘step by step’. By making the model generate text that shows step by step reasoning, it has a minimising effect on the typical erroneous (confabulations/’hallucinations’/failed approximations) that LLMs tend to make. E.g. by adding ‘do it step by step’ to a simple calculation that went wrong (as the one showed above), it would make less errors. These approaches have one thing in common: use the model multiple times to create multiple continuations in parallel, then have some sort of mechanism to select one of all these continuations.

For those somewhat knowledgeable of early AI, this introduces heuristics (tree search — the typical 1960’s AI approach that ran into a wall combinatorial explosion) to LLMs. I suspect this tree search has already been built into the models at token selection level (this may even already have happened with GPT4, it is such a simple idea and quite easy to implement after all). The Tree of Thoughts is more a prompt engineering approach, but these too can lead to new internals, which brings us to OpenAI’s o1/o3 models, that have been created in an attempt to become better at true/false reasoning.

4. Fragmentation/optimisation of the parameter volume and algorithm: Mix of Experts

The ‘set of best next tokens’ to select from needs to be calculated, and as an efficiency improvement some models (we know if for some, it may have been why GPT4 was so much more efficient than GPT3) have been fragmented in many sub-models, all trained/fine-tuned on different expertises. By using a ‘gating network’ the system determines which fragments should be activated during a computation. Then only a few are activated to calculate the ‘set of best next tokens’ from which at random a token is added to the result so far after which autoregression (see above) takes over again. This seems pretty standard optimisation, but apart from some already noted issues from research (like here) I suspect that the gating approach may result in some brittleness. Still, it works. Mix of Experts also sounds a lot better than ‘model fragmentation’, so that works too…

Which long preparation brings us to the point:

The ‘reasoning models’ … aren’t reasoning at all

[Update 6/Apr/2025] After Andy’s comment below I must add that when using the phrase ‘reasoning’ in the context of this post it is a shorthand for ‘logical reasoning’ (or discrete reasoning). This is how the phrase is used in the context of LLM ‘reasoning models’. For humans, we often ‘reason’ by estimation, as this is our main mode of operation anyway — and we humans mostly employ quick and efficient automation. We’re in Uncle Ludwig territory again.]

All these scalings are nearing a point of exhaustion. There is no more data to train on. Increasing parameter count (algorithm complexity) or parameter volume can be done, but the gain is ever less. However, apart from brute force scaling, a separate trick has been added. This trick has led to the so-called ‘reasoning models’.

As became clear rather quickly, approximating correct grammar from token statistics is relatively easy, approximating meaning/understanding from token statistics is harder, and especially hard is approximating logical reasoning from token statistics. The reasoning model (e.g. ChatGPT4-o3) approach has been to train (fine-tune) the model not so much on the generated final result in one go, but train it on the (intermediate) form of a step-by-step way to get a result. The inspiration for this came form people discovering that if you put ‘reason step by step’ in the prompt, the model approximated better as it started to approximate the form of reasoning steps which made the model less prone to going astray.

So, instead of a model trained to be the best approximation of the form of good results directly, it has become trained (additionally) on the form of each fragmented ‘step’ in a good result, but specifically for domains where this reasoning can help. That is why it will be better at scoring on a math olympiad test or the ARC-AGI-1-PUB benchmark as these are specific domains where analytic steps of a certain form help you to provide a better answer. In some areas, the ‘reasoning models’ do worse, though, as Sam Altman has said. There also is a price to pay, reasoning models like GPT-o3 explodes in compute use. Which is not weird given all that extra ‘form’ it has been trained on.

[UPDATE 8/Jun/2025 — though I’ve been sitting on this since April: the impressive performance of reasoning models on for instance the Math Olympiad or ARC-AGI both got some devastating blows recently. Research found that these models may have performed high on Math Olympiad questions, but when a new set of questions appeared and were fed into these models immediately — i.e. the models had not had the change to add the questions and answers in their training data — the models performed dismally (via Gary Marcus; one reason it is smart to follow Gary Marcus’s blog is that he picks these things up quickly). And their performance on ARC-AGI-2 has been dismal too (ARC-AGI-2 is more resistant against brute forcing skill without intelligence). As also became clear: the very impressive scores of GPT4-o3 preview were based on the fact that 75% of the ARC-AGI test set was used during training and unlimited compute during the test. Both together make the GPT4-o3 preview ARC-AGI-1 results from late last year little more than a marketing stunt.]

Fundamentally, the way to describe the ‘reasoning models’ is;

What has been added is a layer of indirection when approximating. Not reasoning.

The indirection doesn’t even need to be ‘reasoning’ at all. It has been so far, as reasoning problems was the issue they were addressing, but theoretically it could be quite something else, though within the constraints of something that has repeatable patterns.

A big downside of indirection is that it is really expensive. Note especially: the extra cost for ‘reasoning models’ is not mostly training cost, it is mostly running cost. If Sam Altman says that even at $200/month and a limit on queries they are making a loss: believe him (this is one of the rare times you should actually believe him). This cost explosion is a real problem. GPT4-o3’s remarkably good score on ARC-AGI-1-PUB seems to have come on a cost of $3000/task, where a human does it at $5/task… Another sign the scaling limit of the current transformer approach is close.

There is another catch as well. For each domain, the form of these ‘reasoning steps’ — and it is that form that is approximated — are different. A model optimised on the form of steps useful in scoring well on a Math Olympiad won’t do well on ARC-AGI-1-PUB. So, we’re entering the approach of narrow solutions like AlphaGo, which plays master level Go very well (but could be fooled by bad/amateur moves 😀) but doesn’t play chess or can do math problems. However, with that above mentioned Mix of Experts (i.e. model fragmentation) approach you can of course create an ever larger set of these capabilities which overall is pretty efficient, and this actually resembles the way humans too have a set of skills that are not always all used at all times. The question that remains open (and I am not optimistic about) how much this ‘set of narrows’ will approximate ‘general’. And if the energy/cost payoff is worth it (probably not). The limited improvement of GPT4.5 — which probably employs the Mix of Experts (model fragmentation) efficiency trick quite heavily — compared to GPT4 seems to bear this out.

[Update 13/Jun/2025 — in part the indirection is often done these days by using something like Test Time Training, or TTT. TTT uses the inputs to create ‘synthetic’ (that is ‘generated’) training material ‘on the fly’ which is then to ‘fine-tune’ the model, as in ‘adapt the parameters’ temporarily based on the input using a loss-function just as happens during original training. This too is an indirection, though slightly different than the basic ‘train on the form of reasoning steps’. It is also a big reason why the ‘reasoning models’ have become so hideously expensive to run; even may run indefinitely if you don’t limit them. These models can get lost in the woods completely: it has been shown that the best answers are in fact the ones that take the least compute. The operational losses of the providers seem to be growing, which means more hype-stories to attract more investors — or at least that has been the pattern so far]

The main reason I am not optimistic about ‘general’ coming from a large set of such indirect-narrows is the observation that while creating a better approximations of certain domain-specific forms of reasoning steps, at the root we’re still approximating on the basis of token statistics. Just much, much more of it on more ‘non-understanding’ parts of text. The ‘reasoning models’ still do not understand. In the same way as the general models do not ‘understand’ but ‘approximate’ correct results, the ‘reasoning models’ do not understand but approximate the form of reasoning steps. And really, that still isn’t reasoning even if it would become a very good approximation of what reasoning will deliver.

None of these are in any way a fundamental shift, they’re engineering the hell out of a fundamentally constrained approach. And the labels given to these approaches are often prime examples of ‘bewitchment by language’ (cf. Uncle Ludwig).

We should add a question: if approximation of reasoning is good enough, isn’t that as effective as reasoning? And the answer can be yes, It is yes when reasoning isn’t sensitive to small errors. It is no when the outliers, the small errors, become essential. But there is a problem: reasoning in itself is a fundamental capacity that is independent from the actual subject. It is thinking in true/false and using that certainty to build edifices. Approximation of the steps of reasoning remains ‘domain-dependent’. It isn’t that ‘free from time and space’ capability. It is for that reason that — even if in a certain domain it is as effective as reasoning — it isn’t reasoning.

In the end, Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), reasoning, remain red herrings. They are mostly irrelevant in the debate, even if ‘narrow’ productive tools can be created this way. The true effect of Generative AI doesn’t have much to do with AGI, being trustworthy, or with not having hallucinations. It seems to be a set of specific ‘narrow’ reliable uses and a wide area of ‘good enough’ (cheap) results.

It seems a waste of time to have to repeat this over and over: forget AGI, it is a red herring in the current discussion on Generative AI. ‘AGI’ discussions distract us from the actual things Generative AI can do (and is doing), which is not AGI but which is producing incredible volumes of cheap not-quite-trustworthy material, amongst which will be some real gold nuggets. A bit like the internet itself or like social media: a lot of low-quality, noise, garbage and junk, but there are some real jewels sprinkled inside it. A lot of junk exists on YouTube, but also some incredibly good material. So don’t disregard Generative AI, and especially don’t disregard the way it will be able to damage factuality (just like social media has been able to do). Because even the so-called ‘reasoning models’ fundamentally do understand Zilch. Zippo. Nada. Niets. Nothing. And there is nothing that has been proposed even (let alone implemented) that truly bridges that gap.

Generative AI delivers a new mode of ‘intelligence’, and trying to explain it with only the old categories is never going to work.

If you like this story or think it is a useful contribution. Please share.

This article is part of the ChatGPT and Friends Collection. In case you found any term or phrase here unclear or confusing (e.g, I can understand that most people do not immediately know what a ‘token’ is (and it is relevant to understand that), that ‘context’ in LLMs is whatever has gone before in human (prompt) and LLM (reply) generated text, before producing the next token), you can probably find a clear explanation there.

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

The fundamental weakness of your argument is this:

“reasoning in itself is a fundamental capacity that is independent from the actual subject”

That is not so. Human reasoning is not independent of actual subject at all.

Pure logical reasoning is an ideal, and we arrived very late at that, during Euclid’s time in geometry, and it has been used only in the highly specialized math domain since then.

Everyday human reasoning is based on heuristics, experience, and most important of all, frequent examination of the consequences of your actions.

What machines need not “true reasoning”, but the ability to check if they are on track, and if not restart or search around.

LikeLike

You’re making a good point. However, the logical part (i.e. our discrete reasoning sense) might predate its pure use as well as written history. I agree that we’re almost entirely an estimating species (and use automations for that, we can call convictions, assumptions, beliefs, etc.), however, there is a difference in actually having that (integrated) very small bit of pure logic (discrete, true/false) or not.

We also are in Uncle Ludwig territory here. “Reasoning” and “pure logic” aren’t the same thing, agreed, (so I must put in a warning, I guess) but in the LLM space “reasoning models” are meant to use logical steps (if then, and such). “Checking if they are on track” begs the question what “checking” entails as you probably very well know, but let’s leave that for another time, shall we?

LikeLike