Sam Altman has said on his blog about Artificial General Intelligence (i.e. human-level-like AI):

“We are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it.”

Sam Altman — Reflections

This, of course, gets the viral-sphere going. Sam, after all, has a megaphone. Now, this is in part traditionally ‘Slippery Sam’, because what is ‘as we have traditionally understood it’? Sam and his compatriots have all the hallmarks of a prophet (if he truly believes what he is saying, a con man otherwise) and thus he deals in messianic results (solving energy, climate, materials, everything), not a lot of hard facts, and if something doesn’t show up, a new prophecy comes along. He also has disciples and followers.

For many, prophecy is enough. Not for some, and we need to be more precise and realistic. So, what is AGI? There are two sources at this time to go to for a definition of AGI.

- There is the very good 2019(!) article On the Measure of Intelligence, by Google engineer and founder of the ARC-AGI benchmark (that OpenAI’s o3 has done remarkably well on, that is, on the PUB-version, more on that later) François Chollet (remember that name).

- And there is the overview and definition (2023) paper Levels of AGI: Operationalizing Progress on the Path to AGI from the serious people at Google DeepMind. This paper can be seen as the result of definitions by Legg (DeepMind cofounder), Goertzel and more. I suspect it is that definition that many people (unknowingly, often) use.

Chollet’s definition of AGI

This is how Chollet defines what you must measure to measure AGI:

The intelligence of a system is a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty.

François Chollet — On the Measure of Intelligence (2019).

What Chollet specifically focuses on are two aspects:

- The system must not simply be good at (a wide range of) skills. It must be able to learn a skill;

- The system must be efficient in learning a skill.

The issue of the latter is that if you throw enough compute at being good at a skill, you can brute-force your way around intelligence. You become good at the skill, without actually having ‘understood’ that skill in an intelligent way. Being good at something without understanding shows up for instance as not being able to handle outlier situations. Gary Marcus is often pointing out the ‘outlier’ problem when someone is silly enough to claim anything AGI-like today.

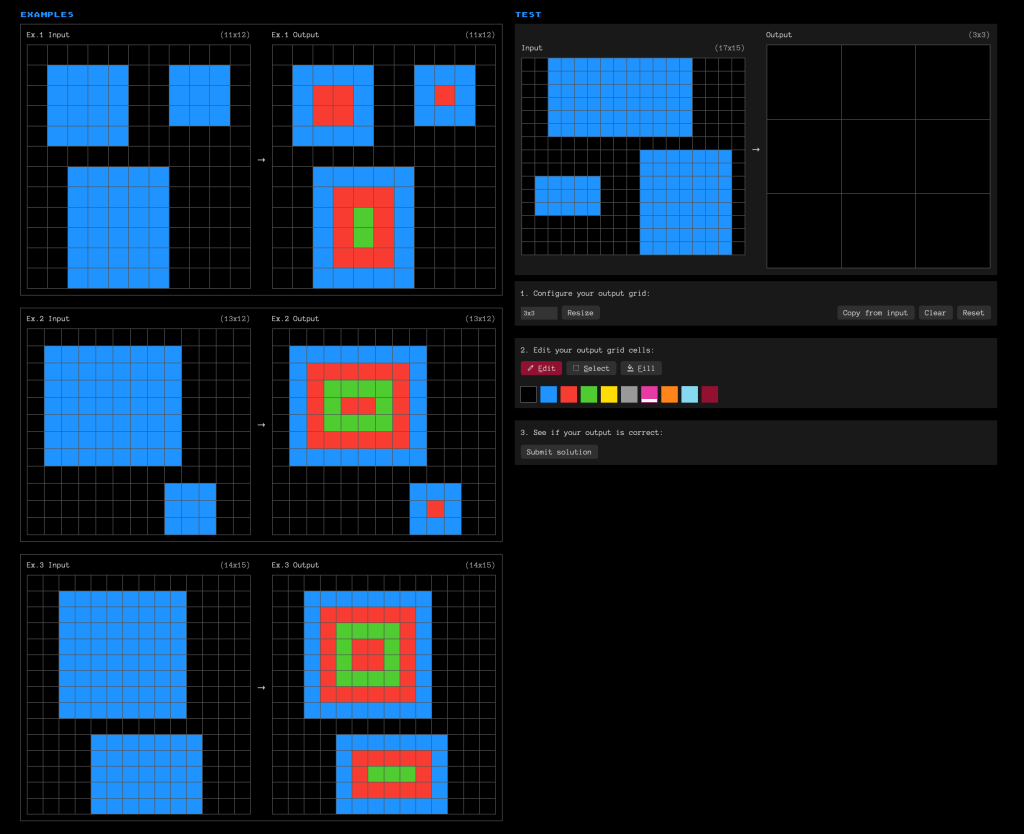

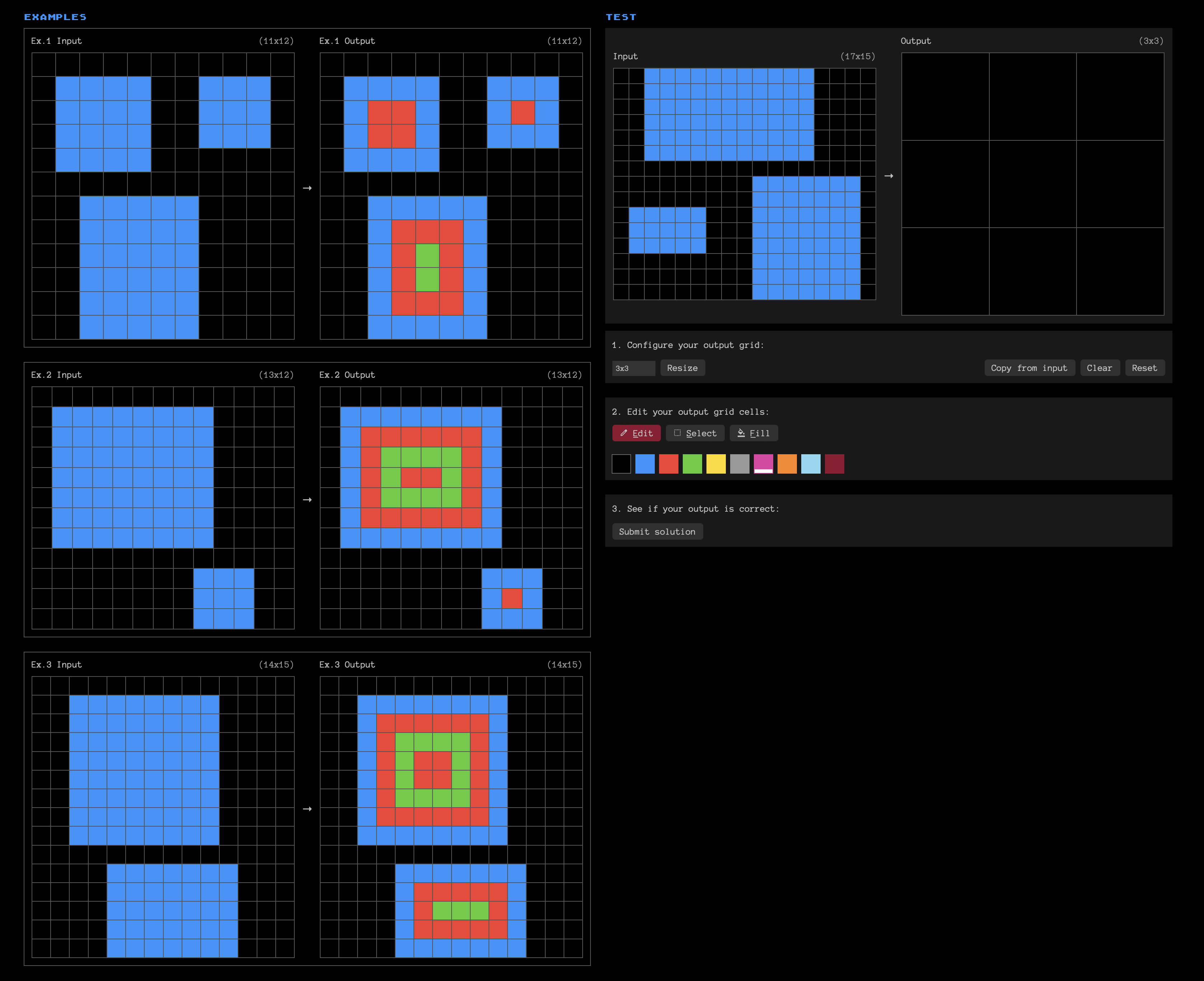

Chollet has actually also created a mathematical foundation for this. And what is more, he has devised a first actual benchmark that tests for this, the ARC-AGI (Abstract Reasoning Corpus — AGI). Now, Scoring good on ARC-AGI doesn’t mean you have AGI. But without scoring good at ARC-AGI you cannot have AGI. The ARC-AGI has been turned into a grand prize at The ARC Prize. Ace it and you’ll win $1 million. It is a set of unpredictable tasks that require you to use your priors in a new way at every test. Here is an example:

You get three examples (on the left), and then you have to give your answer on the right. It is pretty easy to do for humans, but it is very hard for AI, including the likes of GPT4. You can play a daily puzzle here.

DeepMind’s definition of (Levels of) AGI (and the problem)

In DeepMind’s article there is a table:

| Performance (rows) x Generality (columns) | Narrow clearly scoped task or set of tasks | General wide range of non-physical tasks, including metacognitive abilities like learning new skills |

|---|---|---|

| Level 0: No AI Narrow Non-AI | calculator software; compiler | General Non-AI human-in-the-loop computing, e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk |

| Level 1: Emerging equal to or somewhat better than an unskilled human | Emerging Narrow AI GOFAI (Boden, 2014); sim- ple rule-based systems, e.g., SHRDLU (Winograd, 1971) | Emerging AGI ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2023), Bard (Anil et al., 2023), Llama 2 (Touvron et al., 2023), Gemini (Pichai and Hassabis, 2023) |

| Level 2: Competent at least 50th percentile of skilled adults | Competent Narrow AI toxicity detectors such as Jig- saw (Das et al., 2022); Smart Speakers such as Siri (Apple), Alexa (Amazon), or Google As- sistant (Google); VQA systems such as PaLI (Chen et al., 2023); Watson (IBM); SOTA LLMs for a subset of tasks (e.g., short essay writing, simple coding) | Competent AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 3: Expert at least 90th percentile of skilled adults | Expert Narrow AI spelling & grammar checkers such as Grammarly (Gram- marly, 2023); generative im- age models such as Imagen (Sa- haria et al., 2022) or Dall-E 2 (Ramesh et al., 2022) | Expert AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 4: Virtuoso at least 99th percentile of skilled adults | Virtuoso Narrow AI Deep Blue (Campbell et al., 2002), AlphaGo (Silver et al., 2016, 2017) | Virtuoso AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 5: Superhuman outperforms 100% of humans | Superhuman Narrow AI AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2021), AlphaZero (Silver et al., 2018), StockFish (Stockfish, 2023) | Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) not yet achieved |

They specifically write: The “Competent AGI” level, which has not been achieved by any public systems at the time of writing, best corresponds to many prior conceptions of AGI, and may precipitate rapid social change once achieved. If we follow Altman, he claimsOpenAI knows how to build this level.

Now, regarding ChatGPT and Friends, there is an error in this table as I see it: The defining characteristic of ‘General’ is the ability to learn new skills. And according to the table (and many researchers) ChatGPT and Friends tick the ‘General’ box at level 1: Emerging AGI. But that confuses two things:

- Build time ‘learning’: The ‘learning’ (training) that happens when a GenAI system is created;

- Run time learning: The learning it must show when it is in use.

The latter is what Chollet’s ARC-AGI — correctly — tests for. While we call the building of LLMs also ‘training’, this is a simple example of Bewitchment by Language, namely: using the same word and assuming it has the same meaning. Instead of ‘training’ (a form of learning) an AI, we should call it maybe ‘configuring’ an AI (after all: we are looking for the optimal set of parameters giving the desired results).

Really learning means: being able to change your behaviour permanently. For ChatGPT and Friends, this means:

- The Large Language Model (LLM) changing its own parameters

- The LLM changing its own system prompt

- The LLM changing its own algorithms (how its neural net works, the transformer architecture and all)

Neither of these are even remotely close when an LLM is being used, though there is some activity on the first one (without persistency, yet, though).

Now, there is another form of learning that actually ChatGPT and Friends are able to do: In-Context Learning. This is when you give it a couple of examples in the prompt (part of the ‘context’ in LLM-terms). It is also called Few-shot, and you can read about it here (where I illustrate how this technique is used to get (misleading) high skill scores on certain benchmarks). It is of all ways that LLMs learn the weakest. This looks like the ARC-AGI test. And of course, it lacks persistence. Every new puzzle from ARC-AGI is a fresh start from zero.

Why is ARC-AGI hard for LLMs?

The puzzles presented by ARC-AGI have a special characteristic: instances of the puzzles have a high variability, while what we humans would consider the core of doing them is much more stable. Or, in other words: it is much easier to handle that variation if you have mastered the core. Mastering the core, understanding what it is about, is what true intelligence is capable of. If you do, you can handle the outliers much better, because they’re outliers of the variation, but not of the core. ARC-AGI produces instances which do not repeat/reuse a previous pattern. Every puzzle is in a way anew challenge.

Why does a system like ChatGPT work so well on PhD level exams? It might very well be because in the end, the situations asked in the test mostly aren’t ‘outliers’, so they can brute-force scoring well without having mastered the core.

But GPT-o3 aced ARC-AGI, right? Wrong. arcprize.org runs two versions of the ARC-AGI test. One is strictly controlled, for one in terms of how much brute force you may use. This is because Chollet knows that you can ‘buy’ skill performance without having true general intelligence. The public version (ARC-AGI-PUB) is the one GPT-o3 did very well on. Which still is really impressive, truly. But while it did well, it also failed on some very basic puzzles that a human who has the right ‘core understanding’ would never fail on. And because of that, it is thus very unlikely that GPT-o3 is AGI. Take note of what Chollet wrote:

Passing ARC-AGI does not equate to achieving AGI, and, as a matter of fact, I don’t think o3 is AGI yet. o3 still fails on some very easy tasks, indicating fundamental differences with human intelligence.

François Chollet blog post on o3’s results.

Furthermore, early data points suggest that the upcoming ARC-AGI-2 benchmark will still pose a significant challenge to o3, potentially reducing its score to under 30% even at high compute (while a smart human would still be able to score over 95% with no training). This demonstrates the continued possibility of creating challenging, unsaturated benchmarks without having to rely on expert domain knowledge. You’ll know AGI is here when the exercise of creating tasks that are easy for regular humans but hard for AI becomes simply impossible.

And given OpenAI (and Google, etc.) history, me being proven wrong here requires more than another impressive demo without the demo, or impressive benchmark result while we do not know what made it do so well. Was it specifically trained on the best chain of thought steps for ARC-AGI and that Math test? Is that what makes it do worse on some tasks than GPT-4o? Better performance on (a set of?) reasoning tasks at the expense of generality? We simply do not know.

ChatGPT and Friends, are trained on getting maximum performance on variation without getting the core. ChatGPT doesn’t understand language, grammar, or meaning. What it does ‘understand’ is statistical relations between meaningless character-strings (tokens). It has no concept of number, for instance. GPT3 breaks the number 2467 up in two strings “24” and “67” and it breaks the number 8086 up in “808” and “6”. GPT and Friends understand the relations between these meaningless fragments so well, that they can produce results that approximate the results of understanding. So much that we humans experience it as intelligence. It is (a — potentially — very good approximation of) the result of intelligence, without the intelligence. And that fools us humans, because in our experience, having those results is only possible if you also have the core. And for humans that is true. We humans do not have the option to do this brute force.

We need a new term. Let’s call it ‘Wide’ AI

In other words, there is now a new category of intelligence in the world. It can brute force the results of intelligence without the actual intelligence. But it can’t really learn from its own actions. We humans make mistakes, but our mistakes are a completely different category than this new AI. We humans can do Narrow (poorly), we can do General, but we don’t have the means to do this kind of new intelligence ourselves, and we do not have the experience and vocabulary to talk sense about it. It is indeed alien to us.

I propose that we add a new category — Wide: approximating the results of intelligence without having intelligence, on a wide range of tasks — and amend the table as follows:

| Performance (rows) x Generality (columns) | Narrow clearly scoped task or set of tasks | Wide wide range of tasks, not clearly scoped, the system is able to recognise the specific task and adapt to it | General As Wide, but with metacognitive abilities like learning new skills and persistence of these new skills |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 0: No AI Narrow Non-AI | calculator software; compiler | Does something exist here? Complex monolithic systems written in Cobol maybe? | General Non-AI human-in-the-loop computing, e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk |

| Level 1: Emerging equal to or somewhat better than an unskilled human | Emerging Narrow AI GOFAI (Boden, 2014); sim- ple rule-based systems, e.g., SHRDLU (Winograd, 1971) | Emerging Wide AI ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2023), Bard (Anil et al., 2023), Llama 2 (Touvron et al., 2023), Gemini (Pichai and Hassabis, 2023) | Emerging AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 2: Competent at least 50th percentile of skilled adults | Competent Narrow AI toxicity detectors such as Jig- saw (Das et al., 2022); VQA systems such as PaLI (Chen et al., 2023); Watson (IBM); | Competent Wide AGI Could GPT-o3 fit here? Or is it a collection of ‘Narrows’? We do not know. | Competent AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 3: Expert at least 90th percentile of skilled adults | Expert Narrow AI spelling & grammar checkers such as Grammarly (Grammarly, 2023) | Expert Wide AGI not yet achieved | Expert AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 4: Virtuoso at least 99th percentile of skilled adults | Virtuoso Narrow AI Deep Blue (Campbell et al., 2002), AlphaGo (Silver et al., 2016, 2017) | Virtuoso Wide AGI not yet achieved | Virtuoso AGI not yet achieved |

| Level 5: Superhuman outperforms 100% of humans | Superhuman Narrow AI AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2021), AlphaZero (Silver et al., 2018), StockFish (Stockfish, 2023) | Superhuman Wide AGI not yet achieved | Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) not yet achieved |

[Update 15 Jan 2025] Gary Marcus has suggested (linking to this story) to call it Broad & Shallow. I agree that that is more precise than ‘Wide’ as the shallowness is the key difference.

But something is still missing from what people think of when discussing (artificial) Intelligence, I suspect, and that is ‘imagination’.

The key to real intelligence might be imagination

Take the following example:

You’re driving a car. Along the road are many parked cars. Behind the cars is a large meadow, sloping up gently. In the distance on the meadow you can see a school. You instantly recognise the fact that children may be around and may suddenly appear from between the parked cars. You slow down or at least increase your attention.

What is happening here? Well, what is happening is that you do not react to what you see, but to what you — realistically — can imagine. Your behaviour isn’t only governed by reacting to your senses (even a flower closing at night can do that), it is governed by possibilities. By opportunities and risks. As I have written elsewhere, Adriaan de Groot researched the difference between the best amateurs and the top players in chess (he got his doctorate on it in 1946). His observation: it wasn’t that the top players could calculate deeper or more, it was that they saw more possibilities before they started calculating. So, why are self-driving cars so hard to create? Because only reacting to the sensors isn’t enough by far. You need to react to what isn’t there but what could be there. Is ever better reacting to what is there going to be enough to surpass reacting to what could be there? It is possible (after all, we did it in chess, the go example is actually less clear cut), but it might very well be not doable.

This is what happens a bit in the ARC-AGI test from Chollet too, I think.

True intelligence will require realistic imagination. This is related to — as Erik Larson has written in his book The Myth of AI — C.S. Peirce’s abduction based on having mastered many ‘cores’ into ‘making sense’ (sometimes: common sense). We don’t just need an internal world model built from such cores to get intelligence, we need a world model with very fuzzy (and potentially chaotic) boundaries, because we need to be able to go beyond ‘what is the case’.

You’re driving a car. Along the road are many parked cars. Behind the cars is a large meadow, sloping up gently. Between the cars and the meadow is a high fence, apparently brand new. In the distance on the meadow you can see a school. You instantly recognise the fact that children may be around and suddenly appear from between the parked cars, but the fact that the fence is there weakens that assessment. You do not slow down as much but you do increase your attention.

It is absolutely amazing that our brain can do all that with the speed it has (you read my statements, how long does it generally take you to have an opinion about them? that is your mental automation at work) and the energy it uses (about 20W). And I think it will be a while until self driving cars look at the school in the distance or the fence just behind the parked cars.

You’re driving a car. Next to the road is a large meadow, sloping up gently. There are no parked cars. In the distance on the meadow you can see a school. You can see far ahead and there are no children in sight. You do not slow down as much and your attention remains as it is.

You get my drift. The difference between a self-driving car that gets into problems when outliers are presented, and a self-driving car that reacts intelligently may be its imagination. Who’d have figured…?

[Appendix 22 Mar 2025: I strongly suspect (i.e. I am convinced) that the more fundamental bottleneck is that we will never get AGI unless we employ non-digital (non-discrete) technology (such as quantum computing — and that one is very far off — or analog computing: e.g. FPAAs might come in handy). Approximating the value-space richness of reality with discrete values is — regardless of the impressive and useful stuff that may come out of digital technology — mathematically impossible, More on that view later. But as long as we try to scale discrete methods, regardless of the actual architecture, I think we will time and again run into scaling issues when we try to create AGI from it. The so-called ‘reasoning models‘, for instance tend to explode in inference time compute when stuff becomes hairy, while also having to be fine-tuned on the specific form of what ‘reasoning steps’ in a certain domain looks like. Too many warning signs here that AGI is not around the corner. As it already wasn’t in the ordinary LLMs with their lack of understanding/common sense.]

This article is part of the ChatGPT and Friends Collection.

Republished on LinkedIn Pulse

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

I read something explaining Hegel’s concept of Concrete Universals and driving a car was put forward as a really good (modern) example. The 19th century insight is that there is definitely something in the “structure” of reality that allows certain things to work.

There’s something is, of course, something in the structure of language that allows LLMs to “work”. But the structure of language isn’t necessarily the structure of reality. Luciano Floridi is an academic in this field and he seems to suggest that all the automation opportunities address a very low grade of intelligence. I suspect Musk has cottoned onto this. His designs on society, depressingly, might be thought of as capitalism’s counter enlightenment.

LikeLike