As the saying goes: a fish doesn’t see water. That might be us: fish. We humans have been immersed in the Digital Revolution for roughly half a century — give or take 25 years. Now, luckily enough, we are the kind of beast that can exist — although barely these days, try to get by without any IT — outside that ‘water’. With some effort we can look outside-in.

What are the observations and lessons learned that are most important for us, strange amalgam of land animal, surfer and deep diver that we are with respect to IT?

TL;DR?

This is a LONG READ. There is little that can be done about that. Sorry. But, very short: fundamental properties of digital IT lead to unavoidable consequences of the Digital Revolution, a main one being that we’re not heading for a Singularity Point but for a Complexity Crunch.

Let’s start off with a more complete quote:

It is said that fish do not see water, nor do Polar bears feel the cold. Native writers on subjects like those the present work deals with do not even think that anything which has been happening daily in their own immediate surroundings ever since their infancy can possibly be worthy of notice; the author of this work, on the contrary, being a foreigner, is able for this very reason to make a selection of striking facts, and, being also entirely free from local prejudice, is better able to arrive at just conclusions on the matters coming under his observation.

1909, Every-Day Japan by Arthur Lloyd, Section: Introduction by Count Hayashi (Tadasu Hayashi), Start Page xv, Quote Page xvi, Cassell and Company, London. (Google Books Full View) link (see Quote Investigator for a history of the fish-water quote)

The author, by the way, was not right, of course. Culture isn’t math or logic. He might have been free from ‘local prejudice’ but he wasn’t free of his own ‘local’ prejudice. And the polar bear’ reference is clearly nonsense.

But, if we force ourselves to take the outside-in perspective, what do we see? Let’s build a picture from the ground up.

Reliability (trust)

The digital revolution came out of the invention of analog electronic devices that can be used in a way to create binary (on/off) signals, first mechanical and electric switches, then vacuum tubes, then transistors. There were analog computers already available — the earliest neural networks were actually analog computers in the 1940’s — but these are temperamental. Because they are analog, they can for instance be influenced easily by outside circumstances. So, on a sunny day, they may work differently than on a rainy day. Making such devices reliable and predictable was a huge challenge. But it did work. E.g., the 1972 Citroën DS Pallas Injection Éléctronique BW (with airco) we owned for 14 years had a 25-transistor analog computer as part of the Bosch D-Jetronic system (these injection computers in cars only became digital as late as the 1980s).

In one of my talks, I have asked people “how old do you think digital technology is?”. Some think it is since the 1940s-1950s. Some remember the telegraph and Morse code, so go to the second half of the 19th century. But my answer is: around 5000 years at least. Because as soon as you are using discrete elements, be it for arithmetic or writing, you are using a ‘digital’ system. For instance, an alphabet is ‘digital’. There is an ‘a’ character and a ‘b’ character, but not a ‘halfway-a-b’ character. So, digital technology is as old as writing — an alphabet written on paper — or accounting — even accounting the number of fishes you owe by scratches on wood —, take your pick. The fact that the medium is paper or stone tablets or a piece of wood, doesn’t really matter, just as it doesn’t matter if your bits are holes in paper tape, directed areas on magnetic tape, small reflective areas on CD, etc. There is a reason text was one of the first things to be transmitted reliably over electric wires: the source already was ‘digital’.

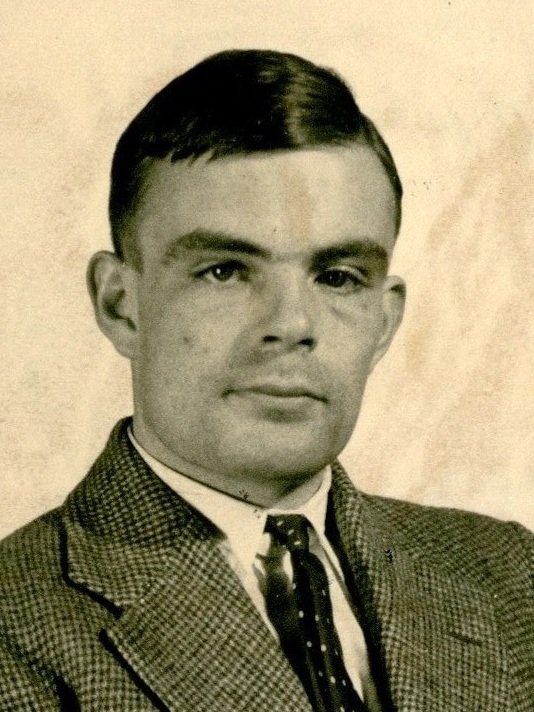

This is how Alan Turing, a founding member of the Digital Revolution told it. We have

“machines which move by sudden jumps or clicks from one quite definite state to another. These states are sufficiently different for the possibility of confusion between them to be ignored. Strictly speaking there, are no such machines. Everything really moves continuously. But there are many kinds of machine which can profitably be thought of as being discrete-state machines. For instance in considering the switches for a lighting system it is a convenient fiction that each switch must be definitely on or definitely off. There must be intermediate positions, but for most purposes we can forget about them.“

Now, the big advantage of digital technology is its exactness, its perfection. There is no doubt if the character is an ‘a’ or a ‘b’ (unless the underlying analog medium fails). There is no doubt that 2+2=4. In the end, everything discrete is equivalent to pure (classical) logic. It is not so that 2+2 is 4 now, but 5 tomorrow, or that 2+2 is 4 here, but 3 there. Pure, discrete, true/false logic is thus free from time and space, it is not physical, it is virtual. Pure (classical) logic is dimensionless (Limits and Dimensions, in Het Binnenste Buiten ISBN 978-90-815196-1-8). This has a huge advantage: when something has become discrete (digital), transmitting the ‘bits’ across space and time becomes easy, because as far as the bits are concerned, there is no time and space. Of course, that doesn’t mean that the meaning we have given to those bits transfers as easily, more about that later, but we can read Plato’s Protagoras 2500 year later in a different part of the world, because of the reliability that comes from its ‘perfection’ leading to an almost perfect reliability of transport of the bits that carry that tale (as long as the bits were made and did not get lost — so sad we cannot read Protagoras these days).

One important element is: Because every little part of logic is so perfect, so reliable, we can create huge constructions of them. The heat from all the wheels and sprockets in a huge physical machine may influence it. If one gear that is next to another gear gets too hot, the heat may affect a not directly related gear next to it, causing it to fail. Analog machines are therefore finicky. A building can fall down under its own weight, the bottom being squashed by the weight of the top. But in a software program with thousands of if’s, the operation of one ‘if’ doesn’t influence another. It can’t get too hot or melt another ‘if’ elsewhere. Millions of ‘ifs’ elsewhere have no bearing on this ‘if’ here. The fundamental dimensionless reliability of pure logic thus makes almost limitless huge combinations of logic possible. And this growth is what we have witnessed over the last half a century or so.

We might say that this utter reliability is akin to a high level of trust. We trust logic because it is so reliable. In our psychology, the same is true. We seek logical argument (true/false) because we can easily trust the mechanism, the mechanism itself is impossible to produce ‘wrongness’. And seeking certainty is a very basic survival mechanism.

Productivity (volume)

The first thing that digital technology was used for was as the ideal substrate for text and discrete calculation. Text, because it was already discretely encoded (a writing system like an alphabet is discrete, remember?), discrete calculation because, well, you get the idea. Calculation may work on non-digital/discrete values, but the math formulas are pure logic, built on the discrete notion of true versus false.

(I am ignoring constructivist/intuitionist math here, but as an aside, if you take L.E.J.. Brouwer’s intuitionist math you will see it introduces a dimension, namely time. Constructivist/intuitionist math is one-dimensional, whereas standard math is zero-dimensional. But I digress, as usual.)

To stress the fact that digital computers can only handle integer values: they cannot handle all values, such as all ‘real’ values. Our spreadsheets might have floating point values, but these are ‘fake’, not real: each is made up of three integers. There is a lot of hidden ‘engineering the hell out of it’ behind the scenes going on to approximate working with analog/real values in digital/integer machinery in a way that makes us not notice the absence of real values (until we do in certain scenarios). Digital computers can only represent an extremely limited set of real values: smart manipulation of integer values is what they do, period. To make matters worse: the ‘floating point’ numbers they can represent are not evenly distributed, we can represent a lot of values around 0, but the bigger a number gets (either positive or negative direction) the less precise we become. The article linked above has a nice explanation. This has consequences (which are normally ignored, but these days we regularly come at points where this is no longer feasible). Aside: watch out for reports on the number of parameters in generative AI models: their size matters too. Twice as many at half the average size is a growth of zero, more calculations with smaller numbers.

Aside: in the 1990s the term multimedia was introduced. This is wrong/sloppy. It was more the introduction of a new carrier medium: bits. This is unimedia, not multimedia. And from the perspective of combining audio, video, text it was wrong too, papers already had text and images. TV already combined audio, video and text. Then of course there was ‘media’ as in ‘the media’. What happened was that the internet got graphics and video and everyone became agog, not thinking clearly. There was this weird guy (😀) who wrote about it in 1995 in an obscure policy background study (section 3.3 Juridisch: De gevolgen van de digitalisering van informatie (unimedia en netwerken) to be precise. I wonder how many people are now going to download that background study about the future of IT, throw it into GenAI Translation and look how much nonsense it contains and chastise that author. Publicly. But I digress, as usual.

Because digital technology was an ideal substrate for anything discrete, such as text encoding (including en-/decryption of text, which was a real boost in the 1940s), and calculating (such as accounting and statistics), these were the first areas to be transferred to computers. Human calculators lost their jobs, computers could do it better and with fewer errors. Human ‘text encoders’ (a.k.a. typists) lost their jobs. Note that writers and readers did not lose their jobs, because that requires not just encoding of text, it requires understanding. (Moving) images too moved to pixels, so there digital technology could now reign as well — technically, not artistically.

Still, we experienced a massive increase of productivity in any domain that could be digitised. I recall the case of an academic hospital I worked with long ago that had digitised their patient records for research purposes. Normally, the department was able to do maybe two research projects each year. And what happened was that an analysis that would have taken six months suddenly only took hours. They went into this expecting to have more time for patients, but what happened was that instead of two research papers per year, they were able to produce twelve. An unbelievable productivity growth, that led not to more time for patients (maybe even less) but to more research output (a sociologist might remark here that this showed what their priorities actually were…). Now, this massive growth in volume of course requires it own handling. Like editorial, publishing, reading by other academics, and so forth. And suddenly we get a new area called research metrics, with statistics, values, a publish-or-perish grant system, etc.. It is a ‘revolution’ in part because it feeds on itself. A bit like the volume growth of the Industrial Revolution drove the need for infrastructure, transport, legal constructs, marketing and advertising, which often again required machines to produce.

When sensors became analog-to-digital converters, suddenly we could handle their output with massive amounts of logic. And such sensors could also be used to give digital feedback to logic that was driving a machine, enabling operating these machines by using logic (i.e. a motor being turned off when a sensor detects a certain signal). When we created digitally controlled integrated physical elements (like step-motors), it became even easier to control elements in the analog physical world with discrete logic. And this is extremely important, because it overcame a constraint of the Industrial Revolution.

[The section below has been made more precise on 2 Feb 2025 by separating the physical automation revolution (late 18th, early 19th century) — which already was about automating (physical) behaviour — and the energy revolution].

If you bring it all back to a single thing, the Industrial Revolution has been a massive growth of the available physical behaviour under human control. Before the industrial revolution, humans and animals provided most of the kinetic power and behavioural skill — with the occasional machine, like water or wind mills. In the Zaanstreek of The Netherlands, a whole pre-industrial machine energy boom played out, powered by mostly wooden wind mills. The invention of a reliable steam engine unlocked the power of fire, as in, a way to turn heat energy into kinetic energy, thus unlocking a huge amount of physical productivity. The use of fossil fuels provided a massive amount of heat energy that powered both the physical and — especially after starting to use oil — chemical side of the Industrial Revolution. In fact one could say that the industrial revolution was made up of two physical revolutions: first the physical automation revolution (initially driven by the automation of work in the cotton industry in the late 18th century) and the energy revolution, which expanded the amount of available energy that could be put to work with or without human skill or physical automation.

I have read that these wooden mills tended to burn down on average every 40 years or so, so instead of owning one mill, it was more secure to own a 1/40 share in 40 wind mills. This was one of the roots of modern capitalism with shareholders, and a funny observation is that the so-called ‘risk taking entrepreneurial spirit’ was born out of a risk-avoidance insurance-like system. The same was true of the shares in risky sea voyages (‘partenrederijen’) and the trade in those shares was a logical consequence that came of it — digressing again.

To direct how this energy is exactly applied, however, often still requires mental productivity. You can have an excavator, which excavates at the speed of many humans with shovels and pickaxes, but you still need a human to operate it. You can have power wrenches in your car factory, but humans have to apply them.

The Digital Revolution changed that, from maybe half a century ago. Suddenly, we could not only code data (like text), but we could also code mental behaviour. And that means that suddenly, an important constraint of the Industrial Revolution — humans direct most of the behaviour — gets weakened. The Digital Revolution thus gave the Industrial Revolution a huge boost. Suddenly, the mental productivity of humans can be multiplied many orders of magnitude, because we can catch a lot in huge amounts of logic, and logic can be automated by digital machinery. Industrial robots being the poster child for this.

So, while the Industrial Revolution was a physical (and chemical) revolution, the Digital Revolution is a behavioural revolution.

The fact that discrete information is ‘dimensionless’ (free of time and space) and the fact that we now have an infrastructure that can operate on it and transport it with almost the speed of light has broken many established patterns in society. Probably most importantly, it has enabled much more ‘globalisation’ and it has very much undermined the power of (brittle, vulnerable) democracies to prevent free markets to turn into pirate capitalism (again).

Brittleness & Isolation

But there is a fly in the ointment. Logic is ‘perfect’ but that also makes it ‘unforgiving’, and ‘dumb’. If there is logic that only works properly when it gets a certain parameter as the value 2 or 4, but not otherwise (it crashes), then a single bit (hand it ‘3’ instead of ‘2’) may crash the entire logical edifice. This is what happened when in 2019 the Dutch national alarm system ‘112’ went down. It may have been implemented fourfold for availability, but the logic was the same, so it simply crashed four times. This is what more or less happened recently with the Crowdstrike error that resulted in worldwide outages: a part of the system assumed there were 21 possibilities, a part feeding it assumed there was one more. IT logic fails, IT systems crash, IT landscapes go down.

And it is not just working or crashing, but working but giving unwanted — potentially even dangerous — results is an even bigger issue.

Ironically, confronted with this fundamental brittleness that is the inescapable other side of the perfection of logic, we add more logic. I am not aware of any numbers, but I would not be surprised if by now 50% of all the machine logic in the world has to do with preventing the logic we want from not working. By the way, I would also not be surprised if by now, more that 95% of the machine logic we employ is there to make the logic we want to work. From physical logic (in hardware), to operating systems, generic libraries, etc..

To make matters worse, these unwelcome inputs may not come from errors. They may be intentional. Bad actors — some extremely sophisticated — make use from IT’s natural brittleness all the time, even if the first step is often duping a human. This is a more abstract brittleness (vulnerabilities), but the foundation is the same.

Inertia & Complexity Crunch

The larger a machine logic landscape becomes, the harder it becomes to change it. Adding to the landscape — new technology, new systems — may be relatively easy, changing it when it has been established, far less so. The reason is simple: a change here may lead to a problem there. Our landscapes are massively interdependent, both vertically (from business logic down to hardware logic) and horizontally. The latter has some really fundamental dependencies: e.g. if your authentication provider fails, you can’t do anything anymore.

So, we might not have the ‘spaghetti code’ of the 1960’s anymore, but we do have ‘spaghetti landscapes’, and unavoidably so. That is why so many organisations struggle with change these days, especially when you’re talking about key elements of your landscape. Such change initiatives no seldom fail, and they almost always take longer and cost more. These days, larger changes in complex landscapes may take many years and cost hundreds of millions of euros. Yes, part of that may be bad management of changes and landscapes, but a large part is unavoidable, a fact of life in the world of the Digital Revolution.

We humans have reacted to this development by trying to fragment these landscapes into manageable chunks by isolation through encapsulation. Here are a few of the encapsulations we created along the way:

• Functions (system code, 1960s–1970s)

• Object-orientation (system code, 1970s–1990s)

• Service orientation (system landscape, 1990s–2000s)

• Agile Development (organisation, 2000s–2010s)

• Containers (system landscape, 2010s–…)

• BusSecDevOps (organisation, 2020s–…)

As you can see, when the Digital Landscapes became so overwhelming an influence on our ability to change, we flexible humans started to organise ourselves around inflexible landscape (that is what ‘Agile’ is: Reverse Conway’s Law).

In part, these isolations are an illusion. Because technically separating two systems and have them communicate via services or messages might make them technically independent, they still are logically dependent. The aforementioned Crowdstrike disaster was a rare example of a deep technical dependency — in this case for Windows and Linux, not for Apple who has isolated (indeed, that again) this kind of logic from its core operating systems — but even if that doesn’t happen, there is still trouble in paradise. You may be happy that your trading system doesn’t ‘crash’ when the system of the exchange goes down, but that doesn’t mean you can trade.

Initially, our ‘isolations’ were technological. But by now, the inertia of IT has started to even have us flexible humans adapt to inflexible machine logical landscapes, I am talking about Agile methodologies that for instance create ‘autonomous’ (an ‘isolation’ of sorts) teams led by ‘product owners’.

A lot of these isolations — starting with IT systems themselves — enable outsourcing, and it is no surprise that we have seen a lot of that over the last 5 decades. Note that even licensing a system that you deploy on your own infrastructure is technically outsourcing. As a general rule: you own what you can change, and the algorithms inside that software that you have licensed are in fact outsourced to the vendor you are licensing the system from (regulation — like the EU DORA act — is catching up to this, I suspect we’ll see a whole certification business growing out of this).

As mentioned above, ‘perfect’ technical isolations are possible — we’re talking perfect machine logic after all — but behaviourally, logically, these ‘isolations’ cannot be perfect. We need each element we depend on to do its job to be able to do our own.

Aside: everybody is talking about the possible effects of Generative AI on our societies. Some see it as a next huge change (either utopian or dystopian), others see through the hype and see a more nuanced picture. But what nobody is yet talking about is the effect that the size of these systems is going to have on our agility. Because here too, size means inertia, for the systems themselves (remember how much re-training costs), sure, but If these systems are going to become founding elements of our societies, how much inertia are they going to create in those societies? If your organisation builds a whole ecosystem around them, how hard does it become to change that? But there are wider consequences too. For instance, is the output of these systems going to slow down the rate of change of languages as everybody starts to use the models? Are these massive systems not going to speed up but instead slow down the change in ideas? All by the ‘weight’ of the volume of their input, parameters, and output? This depends strongly on how much these systems can generalise beyond their training, and so far the outlook for that is rather dim. For more on Generative AI, see my ChatGPT and Friends series.

The Silicon Valley phrase “move fast and break things” might be seen in part as a psychological reaction to the inertia. It might thus be seen as a reverse wording of the reality that it is hard to move fast because in a world full of brittle logic — the digital world — this breaks things. In reality, the ‘breaking’ of the Silicon Valley phrase often has more to do with a breaking of ethics and norms (which by the way are also brittle and thus are landscapes of them — a.k.a. societies — normally slow to change). In organisations too, the inertia is driving some managers to desperately seek for ‘execution power’ to break through the inertia that comes from complexity. Of course, they might end up breaking things that should better not be broken, e.g. pushing for fast change and ending with a landscape riddled with technical debt/risk. But I digress.

Anyway, organisations feel the effect of inertia everywhere these days. We’re not yet acting consciously on it overly much — as it is not seen as an unavoidable aspect of the Digital Revolution but more as a ‘problem of our execution’. Yes, we can execute badly (I’ve seen enough of that during my career) but there is an undercurrent of unavoidable consequences of ‘being digital’. And we might be able to become aware of them as societies.

We’re not on a road to a singularity point. We’re on a road to — and already experiencing — a complexity crunch.

The hypothetical S-curve of the Digital Revolution

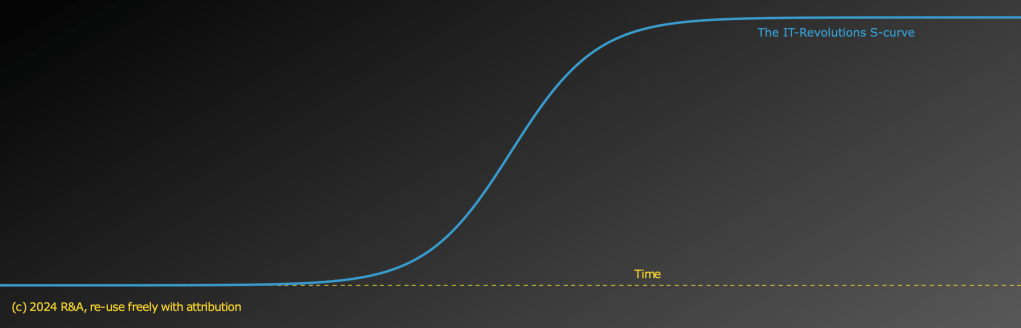

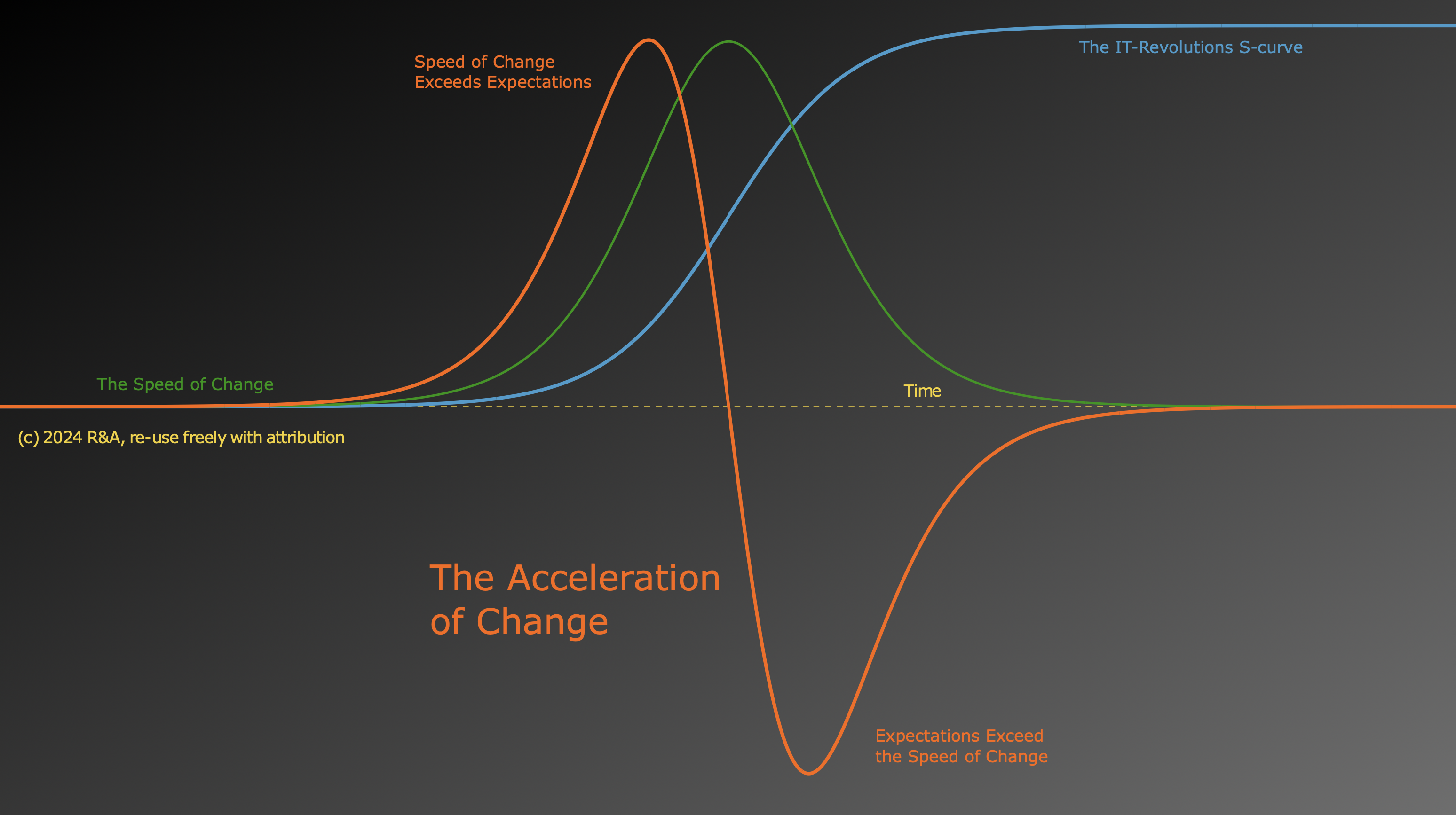

It is reasonably accepted that innovations tend to follow an S-curve. In the beginning there are lots of experiments, then some form ‘wins’, standardisation takes place (e.g. ‘WinTel’ in the 1980s) and a rapid growth phase follows. After a while, society gets saturated and growth slows down (but often variation increases again). This is — we need to keep in mind — a very rough and simplified way to look at a very complex reality, but here it is (images are from slides from my recent EABPM/INCOSE/IASA talks about ‘complexity crunch’):

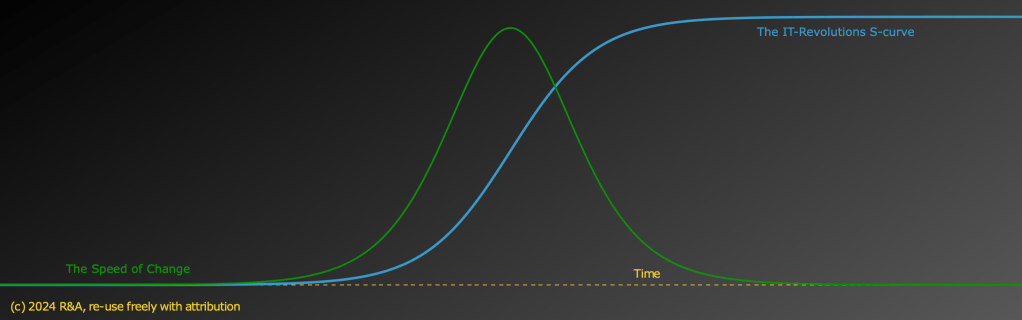

Notice how the start of the S-Curve looks like exponential growth. We’ve experienced that and there are some who have translated that experience to a conviction that the development is exponential until we hit some sort of ‘singularity point’. It also has resulted in the ‘winners’ of the current S-curve (the ‘tech-oligarchs’) predominantly having this cultural exponential outlook. In terms of the speed of change, we get this green line:

If the Digital Revolution follows an S-curve, we must see a slow down at some point. We do see a slow down of the speed of change in many places already, so the question is: is that the beginning of the end of the S-curve?

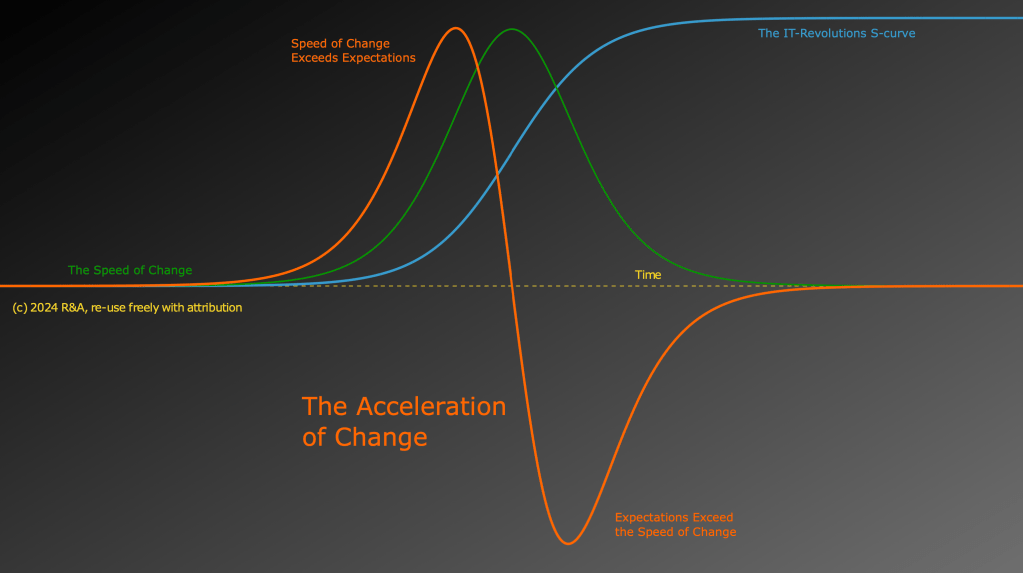

Finally, it is interesting to have a look at the acceleration of change (orange line):

Our experience lags behind and thus, if we are already slowing down (which we see a lot in both organisations and society — see how fast we can change our large complex logical landscapes these days), we are now in the unhappy situation that actual change lags behind expected change, constantly. Most people may not blame IT for that (after all, the speed of change of IT is legendary — it is a cultural given), so they will blame something else. People mostly. Those on the receiving end of this will find little solace in Hanlon’s Razor, even if Hanlon was right.

Strategic essentials for acting in a mature Digital Landscape

Ask your digital architect what to do. Preferably one that understands — i.e. has actual experience with — the complexity of IT, which sadly are in a minority, but, hey, ignorance is bliss (only partly kidding here).

There is much more that I can ever write here (a lifetime of experience bogs me down), but most important are:

- Clean your room! Really. Clean up!. Removing technical debt (which is a misnomer, it is mostly technical risk as in risk of inertia, security breaches and the like), is the most important thing you can do. And do your Life Cycle Management (here and here). There are no two more effective strategic actions you can take as they are foundational for any future agility. And agility is the problem we have gotten ourselves into. Not cleaning up is like having a hospital where the operation rooms aren’t cleaned. Operations may succeed. Patients will die.

- Create your IT strategy NOT simply from your business strategy. Really, the business strategy is important, but doing the classic waterfall from business strategy to IT-strategy today is going to get you screwed, nailed and superglued to it. And since your business strategy changes about 4 times as fast as the key elements of your IT landscapes by now, having an IT-architecture built for now is going to be a major pain a few years from now. You are successful if ‘IT legacy’ becomes a positive term.

- Make sure you have a mature design culture and IT design acumen in the strategy layer of your organisation. This is like the importance to have medical know how in the strategy layer of your hospital. Would you want to go to a hospital that is staffed with only ‘medical economists’ instead of physicians? Execution power without understanding is in most cases going to end in despair.

- Use a collaborative checks & balances approach to design decision making, using consent-based (“I can live with it”), not consensus (“I agree”), or force-based approaches. Nobody can know everything about everything, so without well designed collaboration of all insights on decisions (using approaches like consent-based decision making to make sure decision can be made at all).

- ‘Execution Power’ is really risky and in current reality is more likely to go wrong than right. Imagine:

You’re on the Titanic. The engineers are shouting: “The bulkheads are too low! The rudder is too small! There aren’t enough life boats!”. The sailors mumble: “It has been cold, there will be many more icebergs than usual and further south”. The owners are pressing the captain: “You should be in New York in six days, we desperately need a record!”. And the captain thinks: “I can make it happen. I will employ my execution power.” and says: “Northerly course and full steam ahead!”.

Move fast and break things…

PS. The Fundamental Limit of ‘Being Digital’

Productivity and Brittleness-Inertia are two sides of the same coin — the fact that our Digital Revolution is entirely built on classical true/false logic. We’ve built machines that can do classical logic in unimaginable amounts and with unbelievable speed. Everything we do in digital landscapes is built out of these machine logic elements working on discrete data. But while discrete behaviour has its advantages, it also has a very fundamental limitation. That is probably why digital operation did not end up being the road to intelligence that resulted from evolution. Even we humans who are best at it (as far as we know) are better at frisbee than at logic. And that is why anything that works with reals — like Quantum Computing — is so interesting (but neither a free lunch nor a silver bullet). There is enough to mull over here to fill a section of a book, so I’ll leave it at this.

PS. The next Big Paradigm Change

Social Media and (Generative) AI are going to teach us lessons about ourselves. And at some point, I hope we will see a third historical paradigm shift.

In my estimation, the key cultural paradigm shifts — all driven by our natural drive to know ‘reality’ — may in the end be:

1. The Copernican Revolution: the earth is not that special, it’s not the center of reality*) or its main part

2. The Darwinian Revolution: we — intelligent, conscious — humans are not that special, just another unpredictable outcome of natural processes

3. (Unnamed): We humans might relatively have the most intelligence, but in an absolute sense we’re not that smart

The third — “in an absolute sense, we’re not that smart, so we should design society to that that into account” — is the challenge we humans, as a species, have today. It will be painful to learn the lesson, the questions are: ‘how much pain?’ and ‘will we succeed?’. There is again enough to mull over here to fill a section of a book, so I’ll leave it at this.

*) Actually, if the Big Bang Theory for the universe is correct, we may be the center of the universe, but only because everything in the universe is… (and only if we get a different understanding of gravity, but I digress, as usual)

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

2 comments