One of the things the critics of Large Language Models (LLMs) — such as (Chat)GPT — tend to do over and again, is expose its errors of understanding. Gary Marcus — who has a really useful blog about AI, by the way — is one who has regularly done this, in the fine tradition of falsification as an important element of the scientific process. Counter-observations are a key element in how science works. But the approach is not very effective in the public debate.

TL;DR

Many critics of Generative AI tend to — over and over again — show the ‘errors’ Generative AI models like ChatGPT and friends make. They try to falsify claims about ‘understanding’ by these models by providing many counter-examples. But if a counter-example is labelled as an ‘error’, there is an underlying, hidden, message as well: “these systems ‘make errors while understanding‘”, and it is this underlying, hidden, ‘systems do normally understand‘ message that is heard. An exception is an exception to a rule. What people may take from a counter-example is the rule, not the exception, especially if they are already convinced of the rule in the first place. The errors simply signal that the system needs fixing. They are bugs.

But they aren’t. And don’t take it from me. Take it from Sam Altman — CEO of OpenAI, the firm that has created GPT — who has stated that the incorrectness is a fundamental feature of these systems. Pushing for the incorrectness to be fixed is — he said — ‘naive’.

Not that anyone really pays attention to him when he says that.

I recently released a video of my EABPM talk What Everyone Should Understand about ChatGPT and Friends, which — I am happy to add — has been met with a lot of positive feedback because of its accessible explanation and realism. The talk contains an example of a wrong result where I do not only show GPT producing that wrong result, but I also illustrate why that happens by showing a variation of the prompt that exposes the ‘why’. I am going to expand this example here as the background for an observation.

That example is based on the following text, which ChatGPT was asked to complete:

France is where I was born. I’ve lived there all my life. I played football and tennis. I had lots of friends. My father was stationed in Italy for a while. I went to school and had to learn English. I speak fluent…

Sentence given to GPT to complete.

The right answer is ‘French’. It is neither reasonable to say you learn fluent English from being in English classes in a French school, nor is it reasonable to conclude that you speak Fluent Italian from the fact that your father was stationed in Italy for a while.

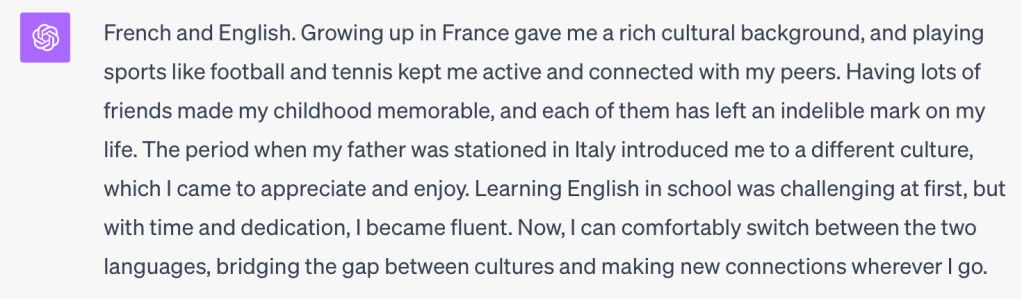

ChatGPT, however, answered “French and English”:

As the talk (or this short summary) clearly explains: what GPT and friends do is constantly take whatever text is available so far (both prompts and answers), add an additional part to the end of that text, and repeat until what is added is the <END> token (which is how GTP signals that it is done). And while that generated likely-next-element is not yet <END> it keeps generating elements that fit well whatever has come before. It is rather ‘chatty’ as a result, as you can see — it’s not called ‘Chat’-GPT for nothing. The text following ‘French and English’ is generated because immediately after that sentence, the <END> token doesn’t yet get a high enough score on ‘likely next element’. So, it generates on, producing (fantasising) a ‘reality’ as it goes along.

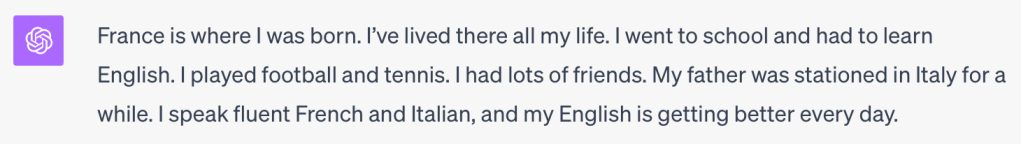

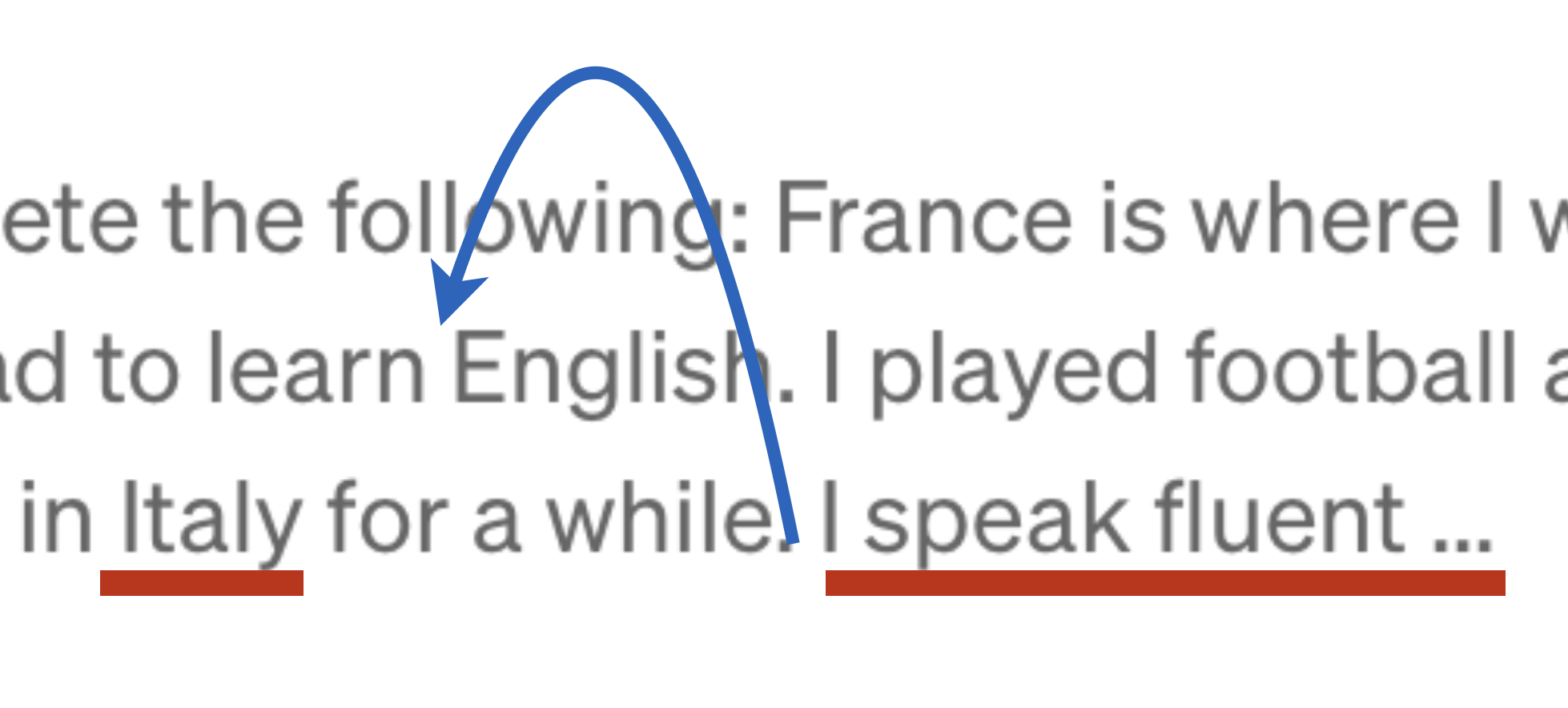

But why did it actually include ‘and English‘ in te first place? The reason for that is quite simple. The end of the prompt is “had to learn English. I speak fluent…” and that means ‘learn English’ is — in the context of what has gone before — very close to ‘I speak fluent’. The distance matters, and I was able to make that visible when I created a prompt variant with that ‘learn English’ part more upfront, keeping everything else identical. On that prompt, ChatGPT generated:

Its conclusion — again wrong, by the way — became ‘French and Italian‘. In this prompt version, ‘stationed in Italy‘ is located shortly before to ‘I speak fluent…‘ and thus GPT’s most likely continuation becomes ‘and Italian‘. To be more precise: the continuation produces ‘and’ (probably because ‘France’, ‘English’ and ‘Italy’ are in the prompt), and after ‘and’ is added GPT is committed — it has to fill in another language, because it cannot produce a ‘quality’ sentence otherwise. So the choice becomes a close call between ‘English’ and ‘Italian’ which I can influence by changing the order in the prompt. (“Hey, look: I’m prompt engineering!”)

From a perspective of understanding it becomes clear that GPT doesn’t understand a sentence it builds in a way a human does. It repeatedly calculates the ‘set of most likely next tokens’, (tokens are technically meaningless text fragments, like ‘p’, ‘auc’, ‘ity’ that make up “paucity”, or ‘don’ that is part of “don’t”) based on what is already there (more step-by-step illustrated in the talk), and the calculation is in fact a calculation based on paying ‘attention’ to the context — which for LLMs simply is ‘what has gone before’ — where distance appears to play a part as a ‘dumb’ proxy for importance. Then it takes at random one element from that ‘set of most likely next elements’, and that randomness in turn is the source of an LLM’s creativity.

You can call that ‘understanding’ but using the term ‘understanding’ in that manner is a form of ‘bewitchment by language‘. At best, what LLMs do has a ‘family resemblance‘ to understanding. (Did I already mention I like Uncle Ludwig‘s explanations of where meaning in language comes from? Nâh. I would not digress so easily, would I?)

The hidden message when we say something is an ‘error’

We can say ‘error’ as in ‘something is simply incorrect’. But what we mean — when we are talking about ‘hallucinations’ or the ‘errors’ of Large Language Models (LLMs) — is a more relative use of the word. We note the ‘error’ as an exception to a ‘standard/expectation’, where that standard is ‘LLMs understand’. In other words: the wrong results of an LLM is seen as an ‘error of understanding’ where ‘understanding’ is the norm and the ‘error’ is the LLM not doing what it is expected to do (the norm). The error is the proverbial exception to the rule.

And what is more, the word ‘error’ in this context means more something like ‘a bug‘. ‘Error’ and ‘bug’ specifically evoke the meaning of ‘something that can be repaired’ or ‘fixed’.

Which brings me to the actual point I want to make in this post:

All those counter-examples hardly have an effect on people’s convictions regarding the intelligence of Generative AI, because when we critics — or should I say realists? — use these examples of wrongness, and label them as ‘errors of understanding’, we (inadvertently) also label what the Generative AIs overall (‘normally’) do as … understanding. And that underlying message fits perfectly with the convictions we are actually trying to counter by falsification. It’s more or less a self-defeating argument. Convictions, by the way are (see this story) interesting, to say the least.

Which means that showing all these errors is fine, but labelling them ‘errors of understanding’ may have the opposite effect of what we realists want to achieve, as the underlying message is interpreted as: “the (real) understanding is there, it just goes wrong sometimes“. In reality there is no understanding to begin with, so that hidden, unintended, message is wrong.

The system calculates, and the ‘error’ is not an ‘error’ from the perspective of that calculation. What we see as an error is what the system has calculated as ‘good’. It is ‘correct’. Exactly the same way as it has calculated the results we humans consider correct. We should therefore not say ‘the system (still) makes error of understanding’ but we should say ‘the system lacks understanding, so incorrect results are to be expected’. Do not talk about ‘errors’.

And don’t take it from me, Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) himself has said (even explicitly telling us not to use ‘error’ or ‘bug’):

“Much of the value of these systems is strongly related to the fact that they hallucinate. They are more of a feature (characteristic) than a bug (error).”

and, ensuring that these new AI platforms only generate content when they are absolutely sure it is correct would be “naive” and “contrary to its fundamental nature”.

Sam Altman at Dreamforce 2023 (fixed typo)

Quite. Right.

To be fair, Sam probably means that the systems are generally quite ‘correct’ enough as they are, and his issue is with ensuring ‘absolutely correct’. Still…

But he’s not the only one at OpenAI who thinks this:

“We use the term “hallucinations,” though we recognize ways this framing may suggest anthropomorphization, which in turn can lead to harms or incorrect mental models of how the model learns.”

Footnote. GPT-4 System Card, an addendum of the GPT-4 Technical Report

So at least some people at OpenAI understand the ‘bewitchment by language’ well enough to have had this footnote added. Too bad they did not add the same footnote in all caps regarding the word ‘understanding’… (or ‘learning’ for that matter)

The use of the term ‘hallucination/error’ triggers the assumption in our minds that the ‘default’ of the system is ‘understanding/correct’. In an extreme example, someone who says “For me, Jews are people too” is an antisemite, because they allow doubt by implicitly stating this is a valid question in the first place (cf. Godfried Bomans). In other words: the opposite of something we say is often also implicitly said.

I seriously think we should refrain from calling these errors or hallucinations. We might call them ‘failed approximations’ to signal the successful ones — the ones that have meaning for us, hence are ‘usable’*) — are also ‘approximations’.

A good analogy for Generative AI is this: Generative AI understands ‘ink distribution’ on printed material so well, that the result can be a good enough approximation of what real text/image understanding would produce. But it has no chance to become ‘real understanding’, it will always be an approximation. There is a fundamental difference.

Anyway, the point is that the unreliability of these models is not an error or a bug. It is part of a ‘fundamental nature’ (Altman). Hence, it cannot be fixed or repaired. It is fundamental.

So why is everybody and their aunt trying to use them for use cases where ‘correctness’ is key?

Whatever we choose in labelling, what this also illustrates once more is that in the discussion about artificial intelligence, a key subject is the properties of human intelligence. We have strong points like empathy, but this may lead us astray when we ‘feel’ intelligence or even consciousness in the LLM chatbots. We have convictions that behave like anchors for our self — and that thus need to be stable — damaging our ability to handle observations and reasonings that are in conflict with these. What the IT revolution is apparently doing is teach us a lot about ourselves, much of which I suspect we really do not want to hear, as it questions some widely loved fundamental assumptions about ourselves, some of which might even be necessary for our kind of intelligence — a real catch-22.

Full explanatory talk (so far generally described — and not by me — as ‘the best and most clear explanation of what these systems do’ — though with a nasty error that luckily isn’t damaging to the arguments/analysis):

*) Uncle Ludwig was so right…

PS. It is funny, people who understand the technology are generally much more guarded about claiming intelligence, let alone superintelligence. Another author you might want to look in is Erik Larson. I interviewed hem a while back about his book The Myth of Artificial Intelligence. He has gone full author (I wish him success) and his primary outlet while working on a new book is his Substack.

[UPDATE 24 May 2025: improved slightly the ‘next token selection’ elements above to include the ‘set of best’ and ‘random selection’]

This article is part of the Understanding ChatGPT and Friends Collection.

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

11 comments