In case you did not read it yet, let me first point you back at a previous post in this series, as it introduces the background on ‘usable messes’ as well as a PDF of the Discussing ArchiMate sections of Mastering ArchiMate 3.2.

ArchiMate has from the start been designed with three fundamental splits:

- The Layers (classic Business-Application-Technology or BAT, see ArchiMate NEXT drops BAT. Now what?)

- The ‘aspects’: Active Structure, Passive Structure, and Behaviour (or columns)

- The split between Internal (‘acting elements’ and their ‘behaviour’) and External (interfaces and services), this happened within each layer for Active Structure and its Behaviour.

It may be stated that the last two have been the most important ones, the first one has already eroded over time with all the added cross-layer relations and is now ever further disappearing. But the other two stand strong.

TL;DR

ArchiMate’s split between ‘external’ and ‘internal’ is a very logical design choice. However, the way it has been implemented is a mess. Half of this, half of that, and a weird mix of overlapping, sometimes ambiguous, abstractions. It could be a lot cleaner and elegant, and that doesn’t requirte that big of a change. 1. Make Service (just like Interface in the Active Structure aspect) part of Process/Function, not an abstraction of it (which even formally means that we cannot model real, concrete services, which we humans tend to ignore). 2. Allow Realisation for any concept to itself to have a clean ‘abstraction’ operator across the board. In other words. In other words: clean up some of the abstraction mess.

So, ArchiMate has always been a deeply service-oriented grammar/language. And these Services are provided via Interfaces. Services and Interfaces are related by Assignment, which says more or less “The Interface performs the Service” just as “The Role performs the Process/Function”.

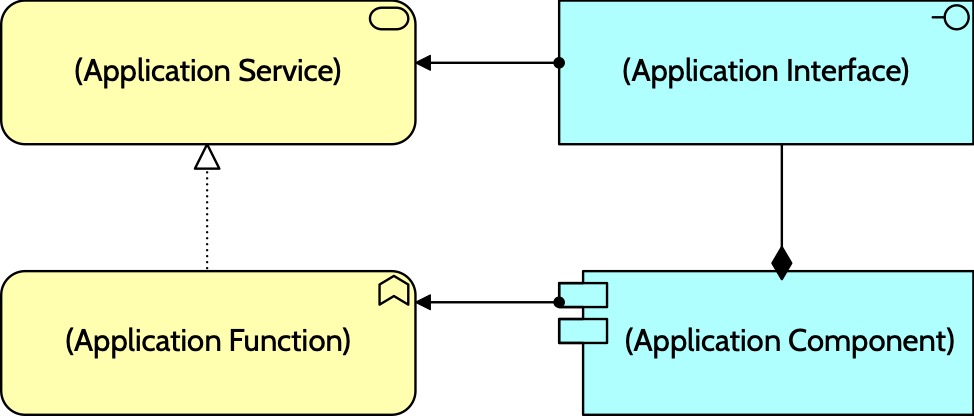

Let’s have a look at that last split. Here is an example from ArchiMate as it is now (in Mastering ArchiMate colours — note ArchiMate is formally colourless)

The active elements on the right are Assigned-To (they perform) the behaviour elements on the left. The top/bottom split on the right, in the active aspect says: the interface is an inseparable part of the application, just like the GUI of MS Word is inseparable from the application. But on the left we see not a whole/part relation, but a Realisation. Why?

For all the Paleoarchimatontology I have been doing, I cannot find a documented real reason. Take the first edition of Marc Lankhorst’s Enterprise Architecture at Work from 2004: “A service is an ‘external’ reflection of the ‘internal’ behaviour that realizes it, analogous to the way in which an interface is an ‘external’ reflection of the ‘internal’ structure behind it.” (p.51, this is more or less repeated on pg. 89 with ‘view’ instead of ‘reflection’). In other places external is often linked to ‘visible’. But I haven’t been able to find a real difference between the two regarding internal/external and why one is an abstraction, but the other one is not.

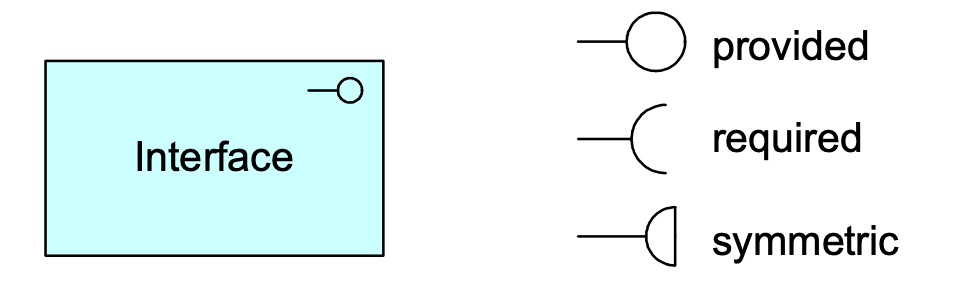

So, it is unclear why, but I can make an educated guess. In part, I think that initially ideas about services were more like ‘interactions’, that the service could only be performed by provider and consumer together. (I recall having read that once, but I cannot locate it anymore, so I might be mistaken). This fits with old notions about provided and required interfaces in PaleoArchiMate. E.g. the first reference manual states: “A business interface specifies how the functionality of a business role can be used by other business roles (provided interface), or which functionality the business roles requires from its environment (required interface). A business interface exposes A business service to the environment. The same Business service may be exposed through different interfaces.” and this can be seen from that time too in the image.

I also suspect that the idea of a service being an abstraction of what goes on in a more concrete sense had to do with the fact that the architects involved wanted to define the service in an implementation-independent ‘logical’ way. After all, it was quite common in that period that those involved in these kinds of discussions were Architects (with a capital A — I met enough of these over the years) and certainly not engineers, developers, builders, plumbers or something of that status. But somehow they probably did not feel comfortable with doing the same with the interface. After all, while they had an abstract notion of service (from service-oriented architecture), they were well aware that the actual Powerpoint User Interface was an inseparable part of the Powerpoint application.

In fact, the situation leads to the interesting situation that an actual, real, concrete, Service technically cannot be modelled in ArchiMate. It is by definition an abstraction as it is Realised. As we are flexible people, we tend to simply ignore that and use that abstract Service to model a real one if we need to.

“Hier kan ik geen chocola van maken”

The most dizzying one in the section about all these abstractions I find this: “[another abstraction,] the distinction between behavior and active structure is commonly used to separate what the system must do and how the system constituents (people, applications, and infrastructure) must do it.”.

Basically, what it tells us here that the behaviour of an active structure element is an abstraction of that element. Not simply “A performs B” as would follow from the subject-verb-object structure of ArchiMate. This probably has its roots in people seeing the Application Function as some implementation-free abstracted description of behaviour and the Application Component as the underlying more concrete behaviour that implements it. Effectively, here we are told that Application Function is both ‘what is performed by the Application Component’, as in the fundamental subject/verb split (‘aspects’), but it is at the same time also an ‘abstraction of the Application Component’ (which is a less concrete version of the same). As the Dutch saying goes: “Hier kan ik geen chocola van maken” (I can’t make sense of this). Or my personal favourite: my clue-meter is reading zero.

ArchiMate works because people tend to ignore these kind inconsistencies in the standard, and just use what they are given as best as they can. Apparently I am not as postmodern as Larry Wall would like us to be (see previous post), because this illogical jumble pains my analytic side. I think this mess can be cleaned up very well. Just do not try to do everything everywhere all at once.

By the way, I noticed that the Realisation from Application Component to Application Component while still mentioned in the section on abstractions (TOGAF Architecture Building Blocks and Solution Building Blocks), was missing from the relationship tables in the ArchiMate NEXT snapshot. Let’s hope the final version will not be a repeat of ArchiMate 3.0.

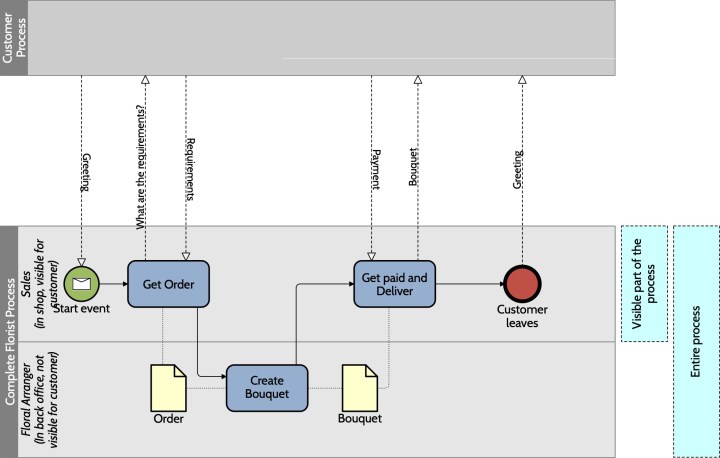

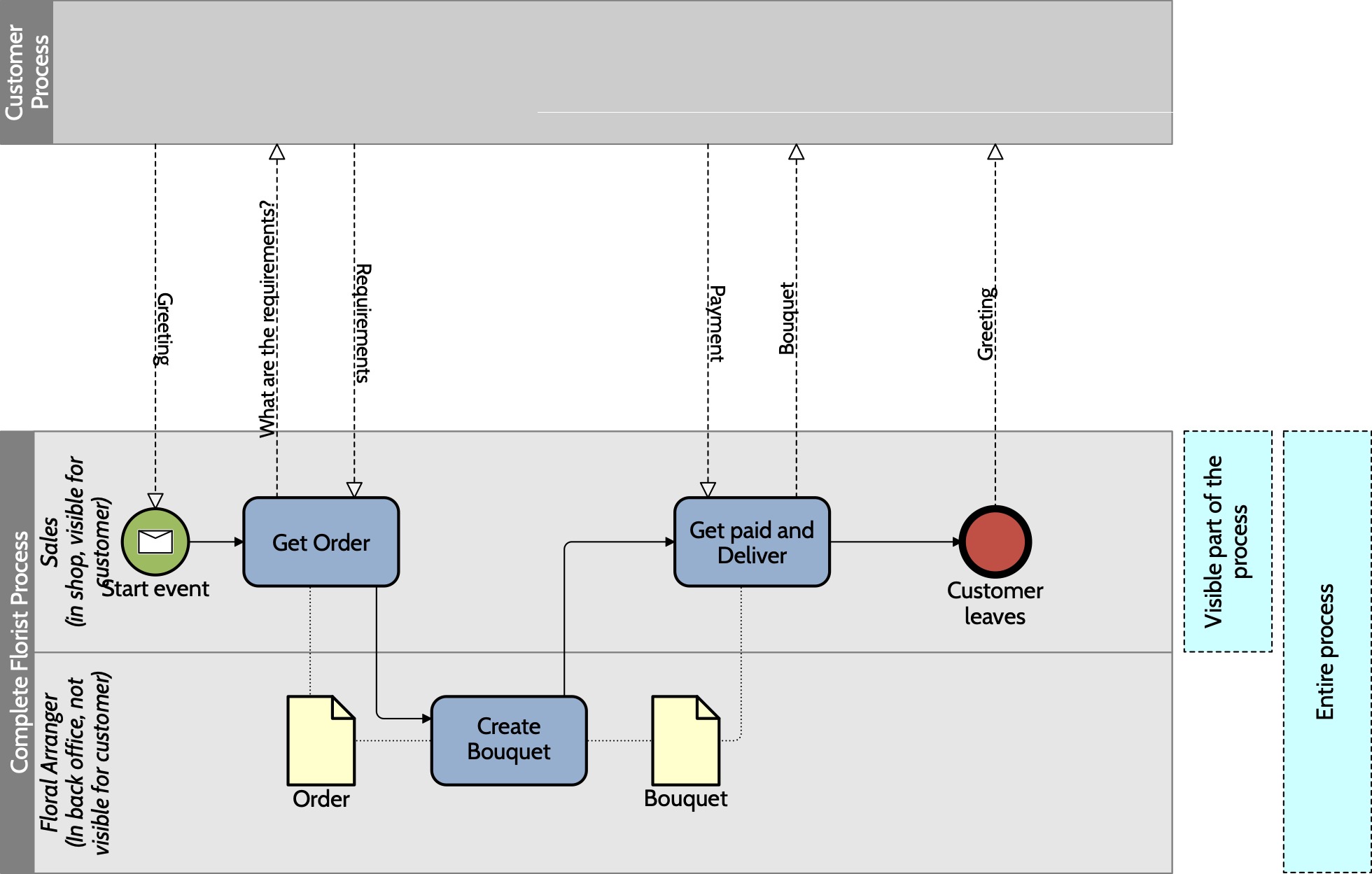

Back to external/internal. Let’s start with a simple example in BPMN of invisible and visible behaviour:

The service is clear here: our flower shop offers flower bouquets. In our flower shop, we have two roles: Sales and Flower Arranger. Let’s say that the interface is the counter and the display of available flowers and of course the way we interact with the sales person. The Flower Arranger works in a room in the back, invisible for the Customer. The Customer only sees the Sales person, they agree on an order, the flowers are collected, then the Sales person goes to the back room, hands the flowers to the Flower Arranger, who creates the actual bouquet, hands it over to the Sales person, who goes back to the counter, gets paid and hands over the beautiful bouquet.

From the perspective of the Customer, only the parts at the counter are experienced. Those are their (‘external’) view of the behaviour of the Flower Shop. So those are what they experience as the service. But if you draw the process in BPMN, you clearly see that that visible part is inseparable from the whole process, not some abstraction of it. So, as far as I’m concerned, let’s be clear here and say that just like the interface is a part of the active structure, the real (concrete) service is a part of the whole process (or function). The — for the user of the service/interface — visible part. This, by the way is the real, concrete Service that ArchiMate can be said cannot model (but we make do).

So, we see the concrete Service, here. But what about abstraction? Isn’t it nice to abstract away from the nitty-gritty and make logical architectures freed from the ugly reality of actual solutions? Personally, I find these more shaman-like products not very helpful in most cases, they often hide more than they clarify, but when communicating with management they may be useful (with ‘the architect’s catch-22’ as a big risk, though). Well, we still have the Realisation relation, don’t we?. Originally Realisation was: “The realisation relationship links a logical entity with a more concrete [it. GW] entity that realises it”. In current ArchiMate 3.2 this has become: “The realization relationship represents that an element plays a critical role in the creation, achievement, sustenance, or operation of a more abstract element.”, and: “The realization relationship indicates that more abstract elements (“what” or “logical”) are realized by means of more tangible elements (“how” or “physical”).” Well, in that case, why not simply have ‘logical’ (‘abstract’, ‘architectural’) services/interfaces Realised by ‘concrete’ (‘physical’, ‘real’, ‘solution’) interfaces? The TOGAF way, (but all the way through)? Have both concrete services and abstracted ones? Not by definition only the messy abstract one? And while we’re at it, why not simply allow every element type to abstract (in the metamodel Realise) itself? It’s clean, elegant, powerful. Abstract away all you like!

The previous post in this short series was: ArchiMate NEXT drops BAT. Now what?. The next one is ArchiMate NEXT: On stories versus maps

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

3 comments