Google recently announced their Willow Quantum Computing chip. The key message Google did put out was this:

- The first is that Willow can reduce errors exponentially as we scale up using more qubits. This cracks a key challenge in quantum error correction that the field has pursued for almost 30 years.

- Second, Willow performed a standard benchmark computation in under five minutes that would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers 10 septillion (that is, 1025) years — a number that vastly exceeds the age of the Universe.

Impressive right? Actually I think it is. Or to be more precise: the first one is hugely impressive and an important step forward.

But, eh, is there a catch?

Definitely, several even, and I’m going to tell you in simple terms. And that luckily doesn’t require a lot of digging into the scientific and mathematical details for us. It only requires understanding normal language. And it’s also not a lot of work for me to explain, as I already did this when — in 2021 — I explained their Sycamore announcement of 2019, which in turn was based on my explanation of quantum computing in 2019. That last article was written because the QM computing hype was really strong at the time. Incidentally, someone working at a QM computing institute has informed me that explanation is correct according to a scientist there, which means that if you want to understand the basics about quantum computing without having to understand physics — or falling for the intuitive but wrong explanation that can be found in many places — that second link really is a good place to start.

The summary of my previous two articles about QM computing is:

- Building quantum computers is incredibly hard (but doable, as we know since 2019). The ‘bits’ in QM computing (qubits) are by definition unstable (since they’re… quantum). Research therefore tries to create QM computing chips that have qubits with less errors;

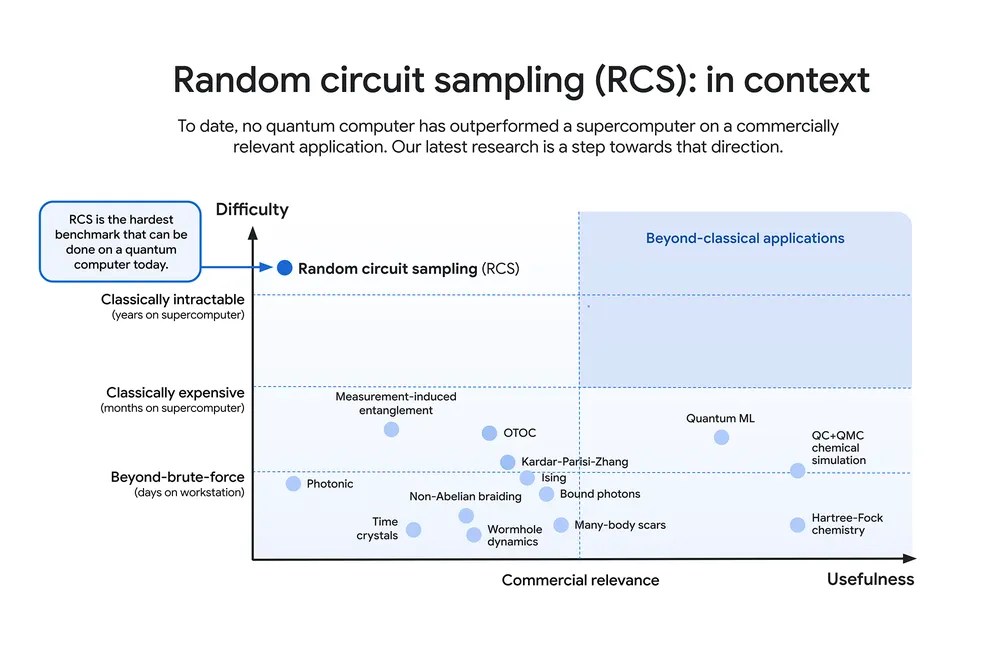

- Using the Random circuit sampling (RCS) benchmark (see below), Google’s Sycamore chip has successfully passed a hardware test for QM computers in 2019, making Google claim ‘quantum supremacy’. As my explainer from 2021 summarises it: Google did a successful hardware test. Before that, we did not even know if we could actually build a quantum computer;

- But while QM computing hardware is insanely hard to build, tune, and control, the biggest problem for quantum computing isn’t hardware: it’s software. We only have a handful of algorithms that can deliver a quantum based speedup, and there is only one that is always mentioned: Shor’s algorithm for factoring large integers into primes.*)

Why is Shor’s algorithm always mentioned? There are two reasons for that:

- Shor’s algorithm scares the hell out of security people (and makes spooks drool) as much of the security in the digital world is based on public-key encryption, and this in turn is based on the assumption that factorising large numbers is extremely hard. Note: in an interesting twist: quantum internet, a much easier to create mechanism than quantum computing, already has the means to stop that breach in its tracks**);

- But even more importantly: Shor’s is more or less the only useful quantum computing algorithm that has ever been invented. And not for lack of trying. It was invented in 1994, which is now 30(!) years ago and it is still the one anyone pushing the hype will mention.

So, let’s forget the dearth of quantum computing algorithms (which is easy, as most people ignore it) and concentrate on the hardware side. Is quantum computing coming?

The state of QM hardware @ Google

Google’s Sycamore chip from 2019 had 54 qubits. Willow has 105, but about half of them aren’t participating in the calculation, they are there to reduce quantum’s problematic (fundamental) error rates. Google has done this by building ‘logical qubits’ (more or less: using multiple unstable physical qubits to get effectively one more usable logical one), which have error-correction. This is the step forward of Google’s Willow QM chip. The way they do this with ‘surface codes’ and ‘repetition codes’ is quite interesting (at least, for people like me), but the fundamental conclusion is that they have a setup which is an important step in what is needed to scale up the hardware.

So, are we almost there?

No.

If you carefully read Google’s blog and published papers you can get a feel of how far we are from an actual quantum computer. The easiest is to simply take them at their word:

With error correction, we can now in principle scale up our system to realize near-perfect quantum computing. In practice, it’s not so easy — we still have a long way to go before we reach our goal of building a large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computer.

Google, Making quantum error correction work, 9 December 2024

In their blogs and papers they sum up quite a list of issues, a few of which are:

- “Quantum error correction looks like it’s working now, but there’s a big gap between the one-in-a-thousand error rates of today and the one-in-a-trillion error rates needed tomorrow.” (here, where they present a glimpse that this might be doable, but with a Hail Mary at the end)

- As stated in a paper: “In addition to a high-fidelity processor, fault-tolerant quantum computing also requires a classical coprocessor that can decode errors in real time.” Or in more ordinary language: the error correction of Google quantum computer actually requires a second digital computer that can keep up with the quantum computing to measure the errors and perform the error correction on the fly by controlling the quantum computer. This is doable for now, but that is in part because:

- Quantum Computers are slow. A single step in an algorithm takes about 10,000 times as long as on a digital computer. But speed this up, and the question may become: can the digital computer used to manage error correction keep up?

In short: Google’s result is really impressive physics. But Quantum Computing definitely still is in the deep experimental domain and far from having a big impact. And I really mean ‘far’. Maybe I should add this as an additional data point. The chip Google uses is a physical thing, like all computer chips. But because these QM chips aren’t digital chips where any next one either does or doesn’t work (and during testing you throw out the few ones that were ‘misprints’), every instance of that same chip architecture is different and behaves slightly differently. This means that after creating an individual chip, the Google researchers have to painstakingly tune their use/control of it to that specific chip.

Which brings me to the reason for writing this post, as I already saw several hype-like messages. Like for instance this one, from one Tim Bajarin at Forbes:

I could have gotten more hyperbolic hype from less reputable sites, but this one is illustrative, exactly because it is a somewhat serious outlet. For one, he honestly starts by admitting he is not an expert. (I’m not an expert either, but at least I was once trained as a physicist and I have read the actual papers). He then says he ‘gained a deeper understanding’ anyway, but his write-up makes several errors that illustrate a rather superficial (mis)understanding and thus reinforces unrealistic expectations. Cue the follow-up from the more crazy people out there.

Which brings me to:

Carefully crafted easily misleading messaging

Google tells us:

Willow performed a standard benchmark computation in under five minutes that would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers 10 septillion (that is, 1025) years — a number that vastly exceeds the age of the Universe

Google, Meet Willow, our state-of-the-art quantum chip, 9 December 2024,

As always (“lies, big lies, statistics, benchmarks”) we need to be very careful with benchmarks (which was written after the Google launch of its Gemini Large Language Model). And this is again the case now.

What is Random Circuit Sampling — RCS — (in layman’s terms)?

Google used a 54-bit QM Computer. Google generated random algorithms — called a ‘circuit’ in QM computing— to run on that QM Computer (so, not useful algorithms, but algorithms with random steps, as if you would create a calculation by randomly applying operations such as addition, subtraction, etc. on your input numbers). Each such an ‘algorithm’ was run millions of times, with all qubits set to 0 initially. The output of running each specific random algorithm for millions of times is a set of millions of output values where some values have a higher chance of appearing and others less so. Earlier research had shown that it was possible to do a limited calculation on the resulting dataset of millions of produced numbers that show that the result is what you would expect if the QM Computer functions properly. Confused? You should be (unless you’re a specialist).

So here is an even simpler way to look at it: Google did a hardware test and found the machine functioned as it should. It has a machine with a low enough error rate and long enough stability that it can reliably run QM algorithms. These algorithms, remember, do not really exist. So it is not surprising that Google (correctly) ends the article with “We are only one creative algorithm away from valuable near-term applications”. True.

When Google on 9 December 2024 put out a video on YouTube about this breakthrough, the scientists (Sergio Boixo, Principal Scientist at Google Quantum AI, Hartmut Neven, Vice President of Engineering at Google Quantum AI, and John Preskill, Director, Institute for Quantum Information and Matter at Caltech — the inventor of the term ‘quantum supremacy’) are in fact very careful:

Boixo: So here at Google, we use this benchmark, random circuit sampling to compare our latest experimental quantum processors with the best classical algorithms running on the best supercomputers that we have available.

Google video Quantum’s next leap: Ten septillion years beyond-classical, 9 December 2024

Neven: We should emphasise that random circuit sampling is not useful for an application. It’s just the entry point. If you can’t win on random circuit sampling, you can’t win on any other algorithm either. The next challenge will be to train this enormous compute power towards a task that people on Main Street would care for.

Basically, what a good result on RCS tells you that if you would have a useful algorithm (that ‘next challenge’), you would have the hardware to run it. That is, if we are able to get to hardware size and quality that is required to run actually useful algorithms. Algorithms which, I repeat, we essentially do not have. So, Preskill adds:

Preskill: And by the way, even if the people on Main Street don’t care, it could still be very interesting. I think the quantum hardware has reached a stage now where it can advance science. We can study very complex quantum systems in a regime that we’ve never had access to before. And for me as a physicist, that’s quite exciting. And with the hardware that people are developing now, which is continuing to improve, we can look for new types of matter that have never existed before and study their properties. That’s already a big deal.

Google video Quantum’s next leap: Ten septillion years beyond-classical, 9 December 2024

In my 2021 article on Sycamore’s ‘quantum supremacy’, I wrote: “You have to admire the physicists for their capability of getting money for physics. What I was inferring there is that QM Computing could be very powerful as a sort of analog computing that mimics physical systems (such as molecules, or fluid dynamics, etc.). So, not as a generic speedup for digital IT problems, but as simulations of physical systems to solve physical problems. Such use might come already when we go somewhat beyond what the current state of the art, such as Google’s Sycamore, can deliver. “He who predicts the future lies, even if he is telling the truth” as the saying goes, but my guess is that the manufacturing and chemical/pharmaceutical world might be among the first businesses to profit from Quantum Computing first and I think it is not unlikely that we will see this within the coming ten years.”

Basically, that is what Preskill says as well. It will be ‘pure physics’ research for quite some time yet — which makes Preskill happy, even if ‘Main Street’ will not care — and maybe we can coax some AlphaFold-like result from it — i.e. some large set of potentially useful materials. I think my ’10 years’ (starting from 2021) for that might be on the optimistic side, but it is possible. Of course the hope that this will lead to those new materials we so desperately need (like room-temperature superconductors) is just that: hope. It could be a hope that comes true, or it could be like the hope of the Alchemists who wanted to create that stone that could turn lead into gold. But mentioning these hopes again adds to the hidden message “useful results are around the corner”.

The literally correct but obfuscated messaging is in Google’s blog as well. Take:

Note the subtitle: “To date, no quantum computer has outperformed a supercomputer on a commercially relevant application. Our latest research is a step towards that direction.” Let me translate that into a clearer phrase (also fixing the weird “step ‘towards’ a direction”): Our Willow quantum computer hasn’t actually outperformed a supercomputer, but in theory, when scaled up massively, and if we fix the outstanding issues and uncertainties it might be able to.

Not quite as exhilarating as what the marketing and communication people at Google — again — turn this into:

- “[…] performed a […] computation in under five minutes that would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers 10 septillion (that is, 1025) years — a number that vastly exceeds the age of the Universe”;

- “Quantum’s next leap: Ten septillion years beyond-classical” — the title of the YouTube video;

- “State of the art performance”

These ‘marketing’ statements that Google is using everywhere are frankly misleading. “State of the art performance”, “performed a computation”, and “Ten septillion years beyond-classical” are like having a car that burns thousands of gallons of gas but isn’t moving at all, but suggesting that it is the fastest car on the planet. It is a suggestion of performance without the actual performance. I almost can imagine serious researchers like Boixo, Neven, and especially the independent Preskill shifting uncomfortably in their chairs when these are the labels put on their words. Or maybe I should say: I hope they are uncomfortable.

When should you — not a physicist/researcher — start paying attention to Quantum Computing?

Probably when a firm stops publishing in scientific journals, opening up all the details of what they are doing. It is why OpenAI, Google, and all the others have stopped publishing about Generative AI (ChatGPT and Friends) other than in vague white papers, cherry-picking video demos, and blog posts. The tricks employed there (note to self: write an explainer about OpenAI ‘o3’ and the ARC-AGI-PUB results [done]) are now closely guarded commercial secrets.

This quantum stuff by Google is hugely impressive from a physics point of view, but just as machine learning took 30 years to go from the basics in the early 1990s to the ChatGPTs of today, quantum computing might easily do the same.

Or quantum computing might in the end turn out to be like nuclear fusion as an energy source. That one has turned out to be so hard that it has been 10 years away for about 60 years now.

In short: keep your head cool and ignore it for now. Unless you’re a science geek.

If you like this story or think it is a useful contribution. Please share.

*) The other more practical use for a quantum computing chip is to directly simulate … wait for it … quantum physics. This is a practical use, but not one you will see all over the place. It will be useful for researchers in for instance materials science. And yes, it could lead to a big breakthrough in areas like that. It is all extremely hypothetical, though. Note: this is more like the analog computers of before the digital revolution. Did you know the first neural networks were analog computers and used on battle ships to calculate targeting? It turned out they weren’t stable enough (eh, wait…), but they did exist (around 1942). (Return to text)

**) Most of the actual encryption on the internet is not public-key, it is shared-key, and this kind of encryption is safe for Shor’s algorithm. In fact, public-key encryption is so slow, that it is only used to exchange a newly generated random shared ‘session’ key, after which the whole encryption is done by shared-key encryption — like AES — which these days is built in to the hardware of most chips except the cheapest ones. If we would have quantum internet we could exchange these shared keys safely, which would give us an alternative, Shor-invulnerable encryption. Of course, if you now have stored all kind of old encrypted data, you could decode that years later with Shor’s, but another problem is that Shor’s algorithm needs really, really large quantum computers to break today’s standard public-key encryption and that is still far off and it is uncertain it is feasible (though Google’s Willow is a step in the right direction). In summary: I’m really not scared that public key encryption will break any time soon and if it does, I suspect quantum key exchange will be with us long before that happens. (Return to text)

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

Hi Gerben,

I may (or may not) do a podcast soon on this Willow business and QC generally. I don’t know much about it, but this was a helpful discussion. My question is: why have any confidence in “ten years from now” or any other timeline when it looks like we don’t have an algorithm to run, and the best we can do is this sampling “as if” one ran? Seems like this is in the vicinity of cold fusion research. What am I missing?

LikeLike

You’re not missing much 😀

Larger and better QM computing machines can still be useful as ‘simulation machines’ for problems in physics, chemistry, biology, comparable with how an analog electronic setup with resistors, coils and capacitors can be a simulation for mechanical problems. The algorithms — such as Shor’s — are specifically needed to use QM computers to speed up digital (discrete) calculations (like factoring large numbers, what Shor’s does).

Another quite different use for QM is not quantum computing but quantum transportation (‘quantum internet’). That is using QM methods to (perfectly?) protect against eavesdropping (which could make Shor’s meaningless again). QM internet is much slower, but you only need to transport a few thousand bits and do the rest on the standard internet.

With respect to ‘ten years from now’: for the hardware alone, I find that already highly unlikely. I think the trajectory of fusion energy so far is probably more appropriate: many decades of hard work (seven decades and counting so far, progress is very slow but it is real) might bring us fusion energy. QM simulations might actually be able to help here. This is in line with Preskill’s original statement in his 2012 paper: “we might succeed in building large-scale quantum computers after a few decades of very hard work”. ‘A few decades’ might become a lot of decades, as it has done with fusion energy.

What I found most noticeable regarding Willow was not so much the ignored lack of algorithms (which I noted in my first post on the issue), but the fact that their error correction requires a digital computer (ML, even) to keep up with the QM computer to do the error correction on the QM computer that is their current step forward. This strengthens the ‘fusion energy’ trajectory for me. As did the observation that each individual chip is (by nature) slightly different and needs its own painstaking finetuning.

The science is not as suspect as cold fusion, but the hype is about as nonsensical as cold fusion hype.

LikeLike