Remember IT changes at breakneck speed? So why does it feel like the opposite when you want change done?

Because it is true. The practice in all organisations in the world is the reverse: IT-change is slowing down. It gets harder and harder. Understandably, and especially given that we’ve been getting used to ‘rapid change’ (or at least the conviction of ‘rapid change’), those in charge can easily develop a view on things that is somewhere between frustration and anger. And the natural reaction is thus one of impatience, sometimes driven by equally hard to avoid hard confrontations with customers, owners, the law, compliance, security threats, etc..

TL;DR

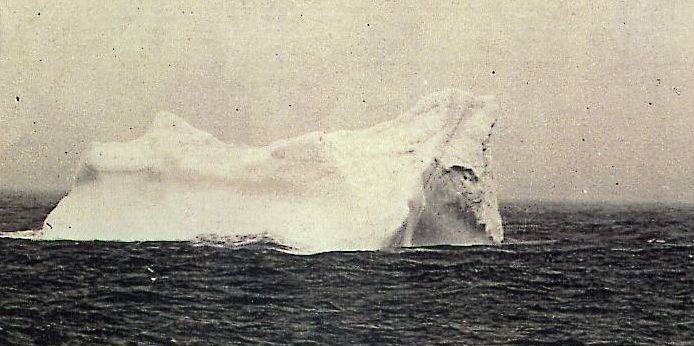

You’re on the Titanic. The engineers are shouting: “The bulkheads are too low! The rudder is too small! There aren’t enough life boats!”. The sailors mumble: “It has been cold, there will be many more icebergs than usual and further south”. The owners are pressing the captain: “You should be in New York in six days, we desperately need a record!”. And the captain thinks: “I have execution power. I can break through. I will be successful.” and orders: “Northerly course and full steam ahead!”.

Move fast and break things…

But — quite different than what most people think — the slowing down of change is an unavoidable effect of ever larger volumes of interdependent IT. In other words: “Hello Humanity, meet the Complexity Crunch!” The complexity shore is as it were turning the IT-change ship. All this is an unavoidable effect of the essential properties of digital IT itself (the long version of the analysis and conclusions: follow the link, this message is also part of a few of my talks, see for instance this one).

“Hello Humanity, meet the Complexity Crunch!”

We’ve seen this slowly becoming worse for a few decades now. And while we get one remedy after the other — technical, like object-orientation, service-orientation, etc., organisational like Agile/DevOps, or mixed like bi-modal or 2-speed IT — the all to real deceleration starts to bite more and more. And that is extremely frustrating if you as an organisation want or need change.

Frustration may breed violence (in a figurative sense). We may try to break the barriers. Again, this is perfectly understandable and logical. It is extremely human, it is true outside IT as well. Hence, one of Silicon Valley’s mantras is:

Move fast and break things

A good example of frustration and attempts to force change is a mantra from Silicon Valley during the last twenty years or so: Move fast and break things. This again is a natural reaction, we hate the barriers to innovation and change and consciously ignoring/breaking them is really a — mental — option. Ignorance, as the saying goes, is bliss too, so we like it.

In corporate reality, this can become “ignore reality in order to move at all”.

But the result of ignorance/ignoring reality is generally a mess when you apply it to ‘technical reality’ instead of ‘societal norms’. Even if you get a result when ignoring the unpleasant technical realities, technical debt/risk, may easily also grow, and everything bad (like vulnerabilities, angry stakeholders, further slowing down) that comes with that explodes too. Society is somewhat malleable and so are the shared norms it is built on — though it sometimes works and sometimes not (Remember Napster? Or if you are such a free speech absolutist that you would allow child porn?) — but technology landscapes are far, far less malleable as digital ‘behaviour’ is extremely brittle.

I tend to use the example below sometimes in my talks about governing complex IT transformations, especially when discussing the risks of architecture principles (following which was an ultimate cause of the project’s down fall). I have gotten this as a first hand report. I am also giving a caveat: psychologists sometimes call memory fantasising about the past so I cannot give guarantees that everything I write here is 100% a correct depiction. But you may read the story below as as close to a factual recounting from some twenty years ago as you can get, as reported to me by a direct witness, without identifying the eal names, numbers, and so forth. Needless to say, one such story isn’t a thing, but I’ve heard more like these, it’s a common complaint of tech people that something like this happens.

Regarding fantasising about the past read this article and watch the documentary that is linked therein: the first episode from the brilliant Netflix series The Mind Explained, which addresses memory.

A Story about Execution Power

In 1998 a large organisation — let’s call it ‘B’ — took the first steps (research) of replacing an older comprehensive IT system that supported their work in a setup of two related organisations that had to cooperate on mostly administrative work. On paper, the — let’s call it X — project started in 1999. The goals were ambitious: next to the two organisations already using the old system together, a third organisation would also become a user of the system, and everything ‘paper’ would become fully digital (all files etc.).

You may imagine something like a huge insurer (our ‘B’), working with an aftercare organisation (let’s call them ‘C’), each with multiple branches, to which a medical partner — let’s call them ‘A’, also with multiple branches — would be added later (at the start of the chain). All three would use the same IT system in their different roles. These days, we would probably set up a setup based on messages and file transport and independent IT at each partner, but that is not the point here. Besides: there really was a need to share working concurrently on the same information, and then messaging can become a problem.

Progress was slow and around 2003 the X project got a restart. The person driving the program from ‘B’ was an experienced driver of getting IT results, so lets call him Max Driver. His approach to management was almost purely ‘execution power’, and he recruited likeminded people around him to manage IT-matters. He personified the ‘autocrat’ style, which tends to become more popular if people become frustrated about change they want but doesn’t come. This popularity might be unavoidable too given our psychology, we see it in society at large as well these days.

Around 2003 my witness — let’s call them Sam Sage — started working for player ‘C’ in that chain of organisations. Sam’s role was in IT policy and architecture. As Sam’s employer — ‘C’ — was a partner in the X project, Sam took a deep dive and noticed some serious problems.

One such serious problem was that the project was working under the assumption that it could ‘rebuild existing functionality with more modern technology, then add new functionality (like those fully shared digital records of cases shared in the ‘chain of partners’)’. A seductive, and thus very popular at the time, but generally misguided idea. In the case of the ‘A’–’B’–’C’ chain, this was a mistake as the actual old functionality was so free-form that some of the branches had implemented ways of working that were not on the radar of the developers. For instance: one very large branch of ‘C’ (mis)used some specific entry field to put the name of the acting team there, so they could later create management reports about the teams. So, inevitably, when the project produced versions of the new system, the users from the large branch of ‘C’ would say “I can’t create reports with this system” and the developers would say “but reporting is not part of the current system!” which, — officially — it wasn’t.

This, by the way, is a favourite example when discussing how you can draw wrong conclusions from IT failures. Management would define the error as an organisational error: “we forgot to involve the users”. And such post-mortem conclusions (“#1 cause of failure: forgetting to listen to your users!”) were quite widely reported at the time. But I would define it as “they made wrong IT judgements that made them wrongfully believe they did not need the users”. It was a lack of IT insight that was at the core.

Anyway.

The biggest problem Sam noticed was that the system was built on two fundamentally conflicting core technologies provided through two vendor products that were combined to build the system, one based on a relational database and the other on a file system. Now this can work, but it is brittle. If anything goes wrong, the database will roll back, while the file system will not, and the result is out-of-sync data, one of the biggest nightmares of IT. And this is exactly what plagued the project. If there was a hiccup, it could take up to 8 hours of painstaking hand work to get the system back in a coherent state. Especially for users at player ‘C’, that sometimes had to handle a mass of simple cases (like hundreds in a few hours), this was unacceptable. Performance was really bad too.

Aside: this fundamentally broken and unfixable setup was the result of applying a then very popular architecture principle. There is a reason I don’t like simplistic architecture principles, they can be extremely toxic in practice, and I like to use this example too as how principles can go horribly (€150 million) wrong.

So, when Sam came back from looking at the project and how his ‘C’ organisation was using the old system, Sam’s internal message to his management at ‘C’ was: “There is a reason the X project is in trouble all the time: the system that ‘B’ has built so far is not easily fixable, it needs a fundamental overhaul. It is not going to live up to the user’s needs, which have been ignored because of a wrong assumption about the possibility of rebuilding ‘existing functionality’. As it is, it is also not going to be stable. Ever.” Sam also shared that with the freshly hired external architect at ‘B’, and that architect immediately saw that these were indeed serious problems. He obviously took Sam’s message home to his superiors, and shortly thereafter Sam was invited to the offices of ‘B’ by their IT manager. They got a cup of coffee and walked into the manager’s office and when they sat down the IT manager from ‘B’ started with:

— “I have heard you have criticised the X project. Well, I had someone like that in here last week and I picked him up by the scruff of the neck and threw him out!”

Sam was stunned and without thinking instinctually and immediately reacted with:

— “And does that help?”

from which moment on there was war (It is not uncommon to run into such office warfare as a result of ‘speaking truth to power’, and it is one of the nastier and more difficult aspects of the job).

Memories — which are often unreliable fantasies even if they feel like stored realities — can be formed by strong emotions. One other memory that has remained with Sam was that a few years later, they were invited to a session with organisation ‘B’, chaired by the big boss — Max Driver himself. The introduction of the first phase of the system had failed again, and Max was visibly angry and frustrated. He let everybody know he was, and that his patience had run out. At one point, Sam remembers him saying (this was in April):

— “No excuses. I’ve had it with all the issues people bring up. We’re going live on the first of October and the champagne will be served in room 202.”

Sam kept his mouth shut, but thought: this is completely unrealistic. If Sam calculated back from that date, there were maybe 6 weeks in total that actual IT changes could be made by the team of the X project. The rest would be needed for tests and all the other things you have to do before going live. So, Sam imagined the project managers going through the large stack of issues:

— “Branch Rotterdam of ‘C’ wants to change the colour of this field so it stands out more clearly and users do not forget putting something in.”

— “We can do that.”

— “Branch Zoetermeer of ‘C’ wants to change the label for this field. It is currently misleading, they think.”

— “That we can do too. We need to set up a meeting with all the other branches to decide on the exact text, but put it on the to-do stack”

— “The case management part that we configure in a vendor’s product must be changed from a file system approach to a database so we get rid of the out-of-sync fragility.”

— “There is no time for such a fundamental change in architecture. Put it on the reject stack.”

By ignoring the know how of the people who could have helped getting this off the ground and instead by simply pushing hard — a certain interpretation of what ‘execution power’ entails — on unrealistic dates, Max Driver indadvertedly made it almost certain that this whole project would never succeed. Sam tells me, the management at ‘B’ kept this pattern up for years. It was pushed back a half year time and again. The main instrument to get results that Max Driver and his team of non-technical people applied was ‘maximum management pressure’. And while that had worked for Max before, this time it was doing the opposite.

Early 2006 Sam organised a meeting of the four leading architects, two from ‘C’ (including Sam), two (both externs) from project X owner ‘B’ — all serious people capable of having an actual IT design discussion (though the ones from ‘B’ were under a lot of strain as there would be an aggressive reaction if they spoke their mind). Sam engineered that they would give a combined judgement to all management teams of all partners. The four actually met in Sam’s home, in Sam’s kitchen, at the kitchen table, discussing what they would tell the management of both ‘B’ and ‘C’, which more or less was: “this is unsalvageable, start over”. Sam worded the memorandum somewhat circumspectly so it would not be too harsh (and acceptable to those two architects from ‘B’) and sent it off. After which both ‘B’ architects got dressed down “how they ever could have given consent to that wording, could they not take it back and say Sam had misunderstood them?”. They did not (for varying reasons).

Shortly before Sam left ‘C’ in 2008, the non-executive board of ‘B’ got involved and the CEO of ‘B’ had to write a letter to that board to explain why the program was delayed again. Sam’s circumspect wording had avoided the explicit use of the word ‘unsalvageable’. Instead Sam had written: “The system is so broken that repair is indistinguishable from starting over.” The people who wrote the letter for the CEO to the non-executive board translated that to “The experts say that the system can be repaired.” Sam considers that a lie, which would have meant that — if found out — the CEO — a nice and very decent person who probably was unaware that they made him lie — would have had to resign.

It was 2014 — 15 years after the initial discussions, 8 years after the architects had delivered their ‘unsalvageable’ judgement — that ‘B’ finally threw in the towel and publicly admitted the whole project had been a failure, even though they had been able to get a few elements in production which they would keep using. I recall they said at the time the project had cost €100 million, but Sam thinks those are only the (visible) ‘out of pocket’ costs, so money paid to vendors, IT development, and consultancy providers and such. He says, “If you include all the time lost by employees of ‘B’ and ‘C’, it must have easily been something like €150 million.”

In 2020 — 21 years after the first activities on the X project — ‘B’ decided to end their strategy of shared data/application use by ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ of IT systems (including X) and start investigating a replacement. In 2023 the then CEO of ‘C’ remarked about long running “problems with stability and adaptability” of system X and implied they would be glad to get rid of it. Sam wasn’t amazed when he heard about these developments. Nor am I. And we both wonder if the old pre-X system is actually still running.

In the case of frustratingly slow corporate change — thanks to the unavoidable inertia of ‘large landscapes of fundamentally brittle logic’ — the autocratic form of ‘execution power’ (ignoring the ‘sailors and engineers’) can go wrong in a comparable way — as the story illustrates. And when five to ten years later the disaster finally arrives in full, we will get another ‘one step too short’ (“we forgot the users”) root cause analysis, and nobody will point to the hard driving manager with ‘execution power’ who — with all their drive to get positive results — in the end did more harm than good. Maybe even fatal harm.

‘Execution power’ in the form of ‘pushing hard’ may make things happen, but even if it does, it may even be the opposite of what you desire.

You’re on the Titanic. The engineers are shouting: “The bulkheads are too low! The rudder is too small! There aren’t enough life boats!”. The sailors mumble: “It has been cold, there will be many more icebergs than usual and further south”. The owners are pressing the captain: “You should be in New York in six days, we desperately need a record!”. And the captain thinks: “I have execution power. I can break through. I will be successful.” and orders: “Northerly course and full steam ahead!”.

Move fast and break things…

(The picture is from the iceberg that sank the Titanic, photographed a few days later with the paint of the Titanic still visible on it)

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]