OpenAI started as a non-profit OpenAI Inc. with a lofty goal: “ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI — machine intelligence that is equal to or beyond human intelligence) benefits all of humanity”. The idea was to be the first and best in the race to AGI, in order to be able to set the rules for it being ‘safe’ and ‘beneficiary’ for humanity.

Sam Altman is now again CEO of OpenAI LLC, though he hasn’t returned to the board of its parent non-profit OpenAI Inc. The structure of OpenAI has been set up so that the necessary commercial activities (you need a lot of money) are checked by the lofty goals of the non-profit.

Underlying all of this is a strongly held conviction: the conviction that AGI — computers becoming as smart or smarter than humans — is potentially around the corner, and that if that happens, we need to prepare, especially for ‘very bad outcomes’. “AGI is Nigh” (“AI-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it is Nigh” — there definitely is more than a whiff of religious end-times overtones here) has been the assumption (the belief) behind all of this. Ilya Sutskever has said this:

Now, AI is a great thing, because AI will solve all the problems we have today. It will solve employment. It will solve disease. It will solve poverty.

Ilya Sutskever in a recent short Guardian documentary (YouTube)

The conflict of November 2023 seems to have been between a board stressing ‘safe’ and Altman stressing ‘speed’ (both convinced they’re on the road to AGI). The board hit the breaks. They are afraid this speed is going at the expense of ‘safe’.

Reuters has reported that a new development at OpenAI — a development called Q* that is reported to dramatically improve handling of math, which is a very weak spot of LLMs — spooked the majority of the board members.

Given vast computing resources, the new model was able to solve certain mathematical problems, the person said on condition of anonymity because the individual was not authorized to speak on behalf of the company. Though only performing math on the level of grade-school students, acing such tests made researchers very optimistic about Q*’s future success, the source said.

Reuter’s reporting.

For those that know about the problems with various AI approaches, ‘vast computing resources’ doesn’t bode well. ‘Certain’ in “certain mathematical problems” is a deep red flag. We’ve been there before in another hype, i.e.:

IBM recently published research that there is a class of problems for which you do not need as much depth (number of steps) on a quantum computer as you would need for the same problem on a digital computer. This has widely been reported on the net as “IBM proves a quantum computing advantage over digital computing” and you may walk away with the idea that quantum computing is around the corner. But in fact what they have found is — again — a small set of problems that may not require as much depth (number of steps) on quantum computing as it does on digital computing. Yes, less steps is an advantage. But small set (of what already is a small set) of solvable problems is a definitive disadvantage. And is there actually a problem in that set that has a practical application? We don’t know. Maybe. If we are lucky.

To be and not to be — is that the answer? Almost 5-year old post on the then hot QM Computing hype. ‘Certain mathematical problems’ is a red flag in the OpenAI reporting as it is like this (special) ‘class of problems’. One learns to recognise the tell-tale signs of over-reporting…

“Acing a test” is yet another red flag. A good analogy here is that in the 1980’s and 1990’s doing good on benchmarks was the ‘acing the test’ of CPUs, so much that some CPU vendors were suspected of optimising their designs for the benchmark only. At the time I wrote an article about benchmarks in a Dutch computer publication explaining how useless those benchmarks often were when talking about real performance. I recall writing: “There are lies, big lies, statistics, medical statistics, and benchmarks”. Especially in LLMs, ‘acing tests’ as a measurement is fraught with risk, as it needs to be very certain the test material has not ended up in the training material one way or another. But even if that is certain and it aces the test, an LLM has the quality that it can ‘ace a test without understanding the subject’.

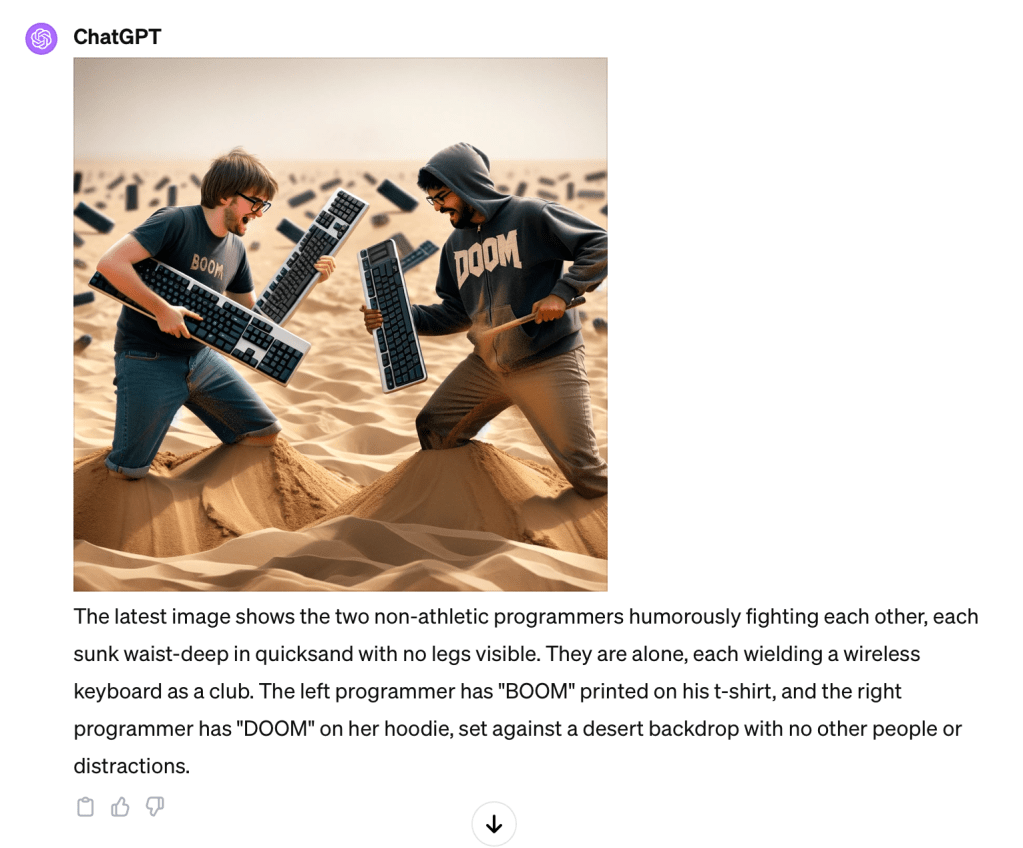

If AGI-around-the-corner is nonsense, we have been witnessing a boxing match on quicksand.

Sam Altman himself is becoming increasingly shamanic on the issue. In October he told his followers:

i expect ai to be capable of superhuman persuasion well before it is superhuman at general intelligence, which may lead to some very strange outcomes

Sam Altman on Twitter, 24 October 2023

Now, there definitely are risks that comes with these new systems, like empowering even more manipulation of us humans. AGI, however, is not one of them. All these beliefs, convictions, expectations about the imminent arrival of Artificial General Intelligence are based on nothing. There is more than enough observation and logic to say this. So, I do call the whole OpenAI fight a boxing match on quicksand. It’s largely irrelevant.

But against a wave of people copying the belief, adding their own doom — “be afraid. be very afraid.” — or boom — “AI will solve all the problems we have today” — expectations fuels the GPT-fever now gripping the planet even more than blockchain or QM computing five years ago. Generative AI has more acceptable (i.e. non-criminal) use cases than blockchain. It is also produces more actual results than QM computing and with 100 million people using OpenAI’s products, and how — with respect to ‘general intelligence’ — these systems are, they will stay around. This will make it so much harder — probably impossible — to keep everyone with their feet on the ground.

The wry observation has to be that history is beautifully ‘rhyming’. We’ve been here before, and more often than people think. I’ve been going down the AI History Rabbit Hole:

To start — and many people are aware — the same discussion raged at the start of the during first AI hype, in the 1950’s–1960’s. Take Feigenbaum and Feldman:

In terms of the continuum of intelligence suggested by Armer, the computer programs we have been able to construct are still at the low end. What is important is that we continue to strike out in the direction of the milestone that represents the capabilities of human intelligence. Is there any reason to suppose that we shall never get there? None whatever. Not a single piece of evidence, no logical argument, no proof or theorem has ever been advanced which demonstrates an insurmountable hurdle along the continuum.

Feigenbaum and Feldman, Computers and Thought (1963) — see below for a humorous reply by Dreyfus.

The discussion is much older, however. It even predates actual working computers. Already in the 19th century, Novelist Samual Butler wrote about intelligent machines and even about the danger of these evolving (Darwin was pretty cutting edge at the time).

Herein lies our danger. For many seem inclined to acquiesce in so dishonourable a future. They say that although man should become to the machines what the horse and dog are to us, yet that he will continue to exist, and will probably be better off in a state of domestication under the beneficent rule of the machines than in his present wild condition. We treat our domestic animals with much kindness. We give them whatever we believe to be the best for them; and there can be no doubt that our use of meat has increased their happiness rather than detracted from it. In like manner there is reason to hope that the machines will use us kindly, for their existence will be in a great measure dependent upon ours; they will rule us with a rod of iron, but they will not eat us; they will not only require our services in the reproduction and education of their young, but also in waiting upon them as servants; in gathering food for them, and feeding them; in restoring them to health when they are sick; and in either burying their dead or working up their deceased members into new forms of mechanical existence

Samual Butler — Erehwon (it GW) ~1872

Butler wrote this potential future as part of a fantasy about a society that had decided that because of this outcome, they would destroy all machines that were not already centuries old — it was satire, but it shows the notion was already there. Funny enough, this is almost exactly what Ilya Sutskever — OpenAI’s Chief Scientist — has said:

It’s not that [AGI] is going to actively hate humans and want to harm them, but it is going to be too powerful. And I think a good analogy would be the way human humans treat animals. It’s not we hate animals, I think, humans love animals and have a lot of affection for them, but when the time comes to build a highway between two cities, we are not asking the animals for permission, we just do it because it’s important for us. And I think by default that’s the kind of relationship that’s going to be between us and AGIs which are truly autonomous and operating on their own behalf.

Ilya Sutskever in this short Guardian documentary about him (YouTube, opens at quote). (It. GW)

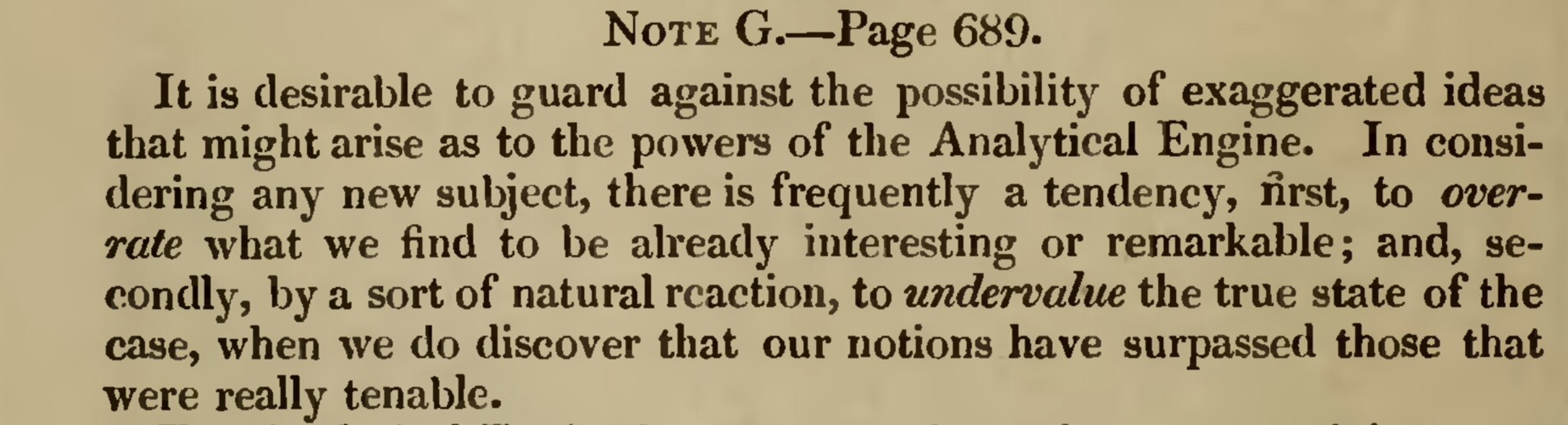

Sutskever echoing Butler is funny enough, of course, but we can go even further back to the time of Charles Babbage who — on paper — invented the first ‘programmable computer’: The Analytical Engine. Babbage gave lectures in Turin and impressed Menabrea, later a prime minister of Italy. Menabrea wrote a treatise about Babbage’s ideas in French. The mathematician Ada Lovelace translated this around 1842–1843 from French to English for it to become part of Richard Taylor’s Scientific Memoirs Vol III. She added several very insightful notes (as she probably understood better than anyone what was being attempted by Babbage — he even told people she corrected an error of his), one of which contains this warning about ascribing intelligence to machines, but given as a general warning if something ‘new’ comes along:

It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that might arise as to the powers of the Analytical Engine. In considering any new subject, there is frequently a tendency, first, to overrate what we find to be already interesting or remarkable; and, secondly, by a sort of natural reaction, to undervalue the true state of the case, when we do discover that our notions have surpassed those that were really tenable.

Mathematician Ada Lovelace (~1842): Translator’s Note G from a translation of Menabrea’s Notions sur la machine analytique de M. Charles Babbage

Yeah. This happens all the time. But do we learn…?

PS. I tried to get Midjourney and DALL•E to create an image of two computer programmers waist-deep in quicksand trying to hit each other with a keyboard. It was a beautiful illustration of a complete lack of understanding by these systems. Is it at all possible to generate this? The funniest was ChatGPT providing an image with its own description where the description and image did not match at all:

PPS. Recall the quote from Feigenbaum above. Dreyfus suggested rather sarcastically (a trait that worked against him, people suffer fools gladly, but caustic experts less so — there is a lesson somewhere here):

Enthusiasts might find it sobering to imagine a fifteenth-century version of Feigenbaum and Feldman’s exhortation: “In terms of the continuum of substances [that metals are all a single substance which means we should be able to turn ‘baser’ metals such as lead into gold – GW] suggested by Paracelsus, the transformations we have been able to perform on baser metals are still at a low level. What is important is that we continue to strike out in the direction of the milestone, the philosopher’s stone which can transform any element into any other. Is there any reason to suppose that we will never find it? None whatever. Not a single piece of evidence, no logical argument, no proof or theorem has ever been advanced which demonstrates an insurmountable hurdle along this continuum.”

Hubert Dreyfus — Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence (1965). I am also reminded of the relation between Ilya Sutskever’s description of how AI will solve all society’s problems above and Paracelsus’ panacea.

More on human convictions and their role in human intelligence here: On the Psychology of Architecture and the Architecture of Psychology

The Oct 2023 EABPM presentation explaining what ChatGPT and friends really do here: What Everyone needs to understand about ChatGPT and Friends (40min video) and the excerpt of two key elements as a guest blog on Erik Larson’s substack here: Gerben Wierda on ChatGPT, Altman, and the Future and the issue of ‘understanding’ by GAI from that talk here: The hidden meaning of the errors of ChatGPT (and friends)

This article is part of the Understanding ChatGPT and Friends Collection.

[You do not have my permission to use this article for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless your system doesn’t misrepresent its contents and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

Well written and based on good research! Thanks for this article.

LikeLike

Thank you. If you like it, actively helping to spread is appreciated 😉

LikeLike