A few years ago, a product owner in an organisation with an on-premises infrastructure wanted a couple of large Tomcat servers for big data operations. They needed to be ‘big’ in one specific property: memory. They required servers with at least 256GB RAM.

– “No can do”, the infrastructure people said, “our maximum is 64GB RAM. If you need more, you need to get an exception from the architects”.

– “Wait”, the product owner of the big data system replied, “where do I find the rule to which I have to ask for an exception? What am I actually asking an exception on?”.

The answer was that the 64GB limit had been decided on when the ‘solution design’ of the VMware environment had been created and approved, several years before. It was rule that was never published as such — as many other rules, such as generic rules on secure protocols, etc. often are — making it rather impossible for the Product Owner what he had to comply with. The 64GB RAM max design decision was pretty healthy at the time. If your Virtual Machines have too much RAM, it becomes hard to shuffle them around between servers and that severely limits the optimisation the VMware hypervisor environment can manage.

TL;DR

We tend to think of requirements as ‘incoming’ elements for our designs. But what we not always explicitly notice is that we also create many ‘outgoing’ requirements in our designs, often in the form of ‘constraints’ of the ‘users’ of the products that come from those designs. These requirements lead a hidden existence most of the time, and that invisibility makes our decision making sometimes less efficient.

What if we would make our outgoing requirements explicit? And how could we manage these dependencies? For that I created an actual small demo solution — built as a plugin for Confluence — to manage solution designs in a library that links them and the requirements they give to each other in a dependency network that goes beyond what a basic Wiki can do.

The story about the RAM limit made me think, and it struck me that we tend to focus on requirements as something a solution design has to conform to (grapple with), but we seldom think of the way that same solution (design) sets requirements for its own ‘environment’, especially the ones that use the solution (e.g. as a platform to deploy something on). So, I came up with the phrase outgoing requirements, and I started to argue that our designs should mark those requirements explicitly in a solution design.

But I wanted more. Because in our landscape (network) of systems, we have many such — effectively hidden — requirements. Suppose your big data solution runs on a tomcat server. The requirements can be hidden pretty deep: VMware (sets 64GB RAM max) — Linux — Tomcat. How would that product owner that requires a 256GB RAM Tomcat server ever find out that the VMware systems has a constraint that travels all through the network until it reaches him? I’ve noticed that we often have many levels of dependency (I counted 7 ‘development-deployment’ levels at one point) So, I visualised a Design Library, a setup where all our designs would live and where the dependencies would be automatically managed.

The obvious solution — if you know that I have written a little book about ArchiMate modelling — to use a modelling language such as ArchiMate and model the ‘network of requirements’ between solutions. It is made for that kind of work. But that solution comes with a drawback: everybody who maintains designs should do so in that single model, so they all need to become modellers and they all need to use that single model. I could not imagine having all our DevOps teams and DevOps Engineers work with architecture modelling tools. That, I knew, was impossible to force upon most organisations, so I started to think about a solution that would give people the standard ‘document-feel’ editing of their solution designs, while enabling dependencies on a finer-grained scale than “Linux depends on VMware” (and good luck reading almost all of the designs to find out what your constraints are).

The solution I came up with is to use a Wiki (as many organisations already do), and have elements in that Wiki to manage the dependencies between the designs. That way, every solution design would have immediate access to all the (inherited) requirements. Making that usable does require some design choices, but if that works, everybody can still produce their storied-design in the form of a ‘document’ (the Wiki page) while under water insight in the fine-grained dependencies is being managed.

An important ‘aha’ moment came when I realised that policies are simply outgoing requirements as well. They are outgoing requirements from the ‘enterprise’ as a ‘system’ to its internal parts. The summary of which is: policies are a form of design decisions (and can be managed likewise).

It turned out pretty hard to explain this, so I decided to show it, following the scenario-writing course I did many decades ago: “Don’t tell them. Show them”, but I digress, as usual.

I.e. I built a small demo.

Keeping my technical skills active is — I think — an important part of my job, as understanding the possibilities and limits of technology is important for whatever I say to be realistic. As with all skills: use it or lose it. For the demo I decided to use Confluence Cloud and I built a basic plugin using Atlassian Forge. Forge is built on top of React, so I had to freshen up the marginal Javascript skills I developed a few years before and learn React. The whole demo took me about 4 weekends: learning Confluence, setting up Confluence development, learning React — thank you, internet —, and building the plugin.

I built a plugin, that has a couple of Wiki-page snippets:

- Defining Outgoing Requirements and Design Decision Stories (another element that really helps in creating good designs — see below) structurally

- Marking a Decision Story as an Exception of an Incoming Requirement

- Managing dependencies between designs and displaying inherited requirements

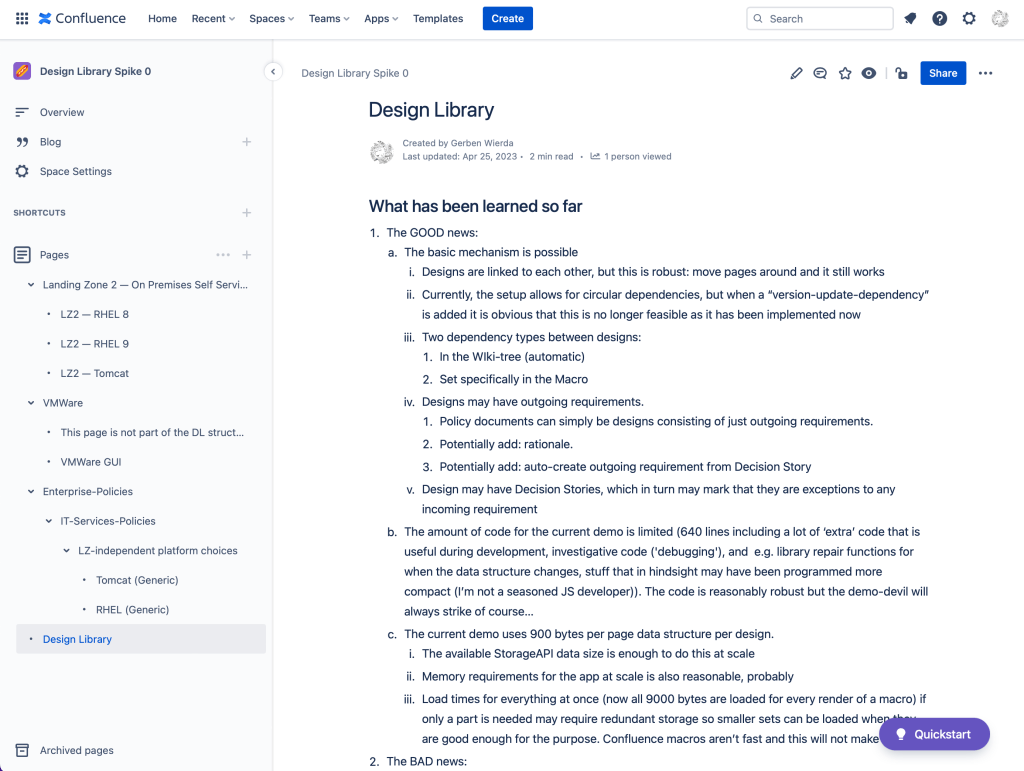

A Wiki generally has a tree like structure, so I decided that dependencies within the tree are automatic (which means you do not have to explicitly set them). So, in the light of “Don’t tell them. Show them.” here is how it looks.

On the left you see the Wiki tree structure. We have a hypothetical enterprise that has several ‘Landing Zones’ (I use Landing Zone as a way to delineate coherent — and thus more or less holistically designed/managed — setups of hosting, development, and deployment). The Landing Zone 2 here is a setup where the DevOps teams can use platforms through self-service (i.e. like the public cloud, but here running on underlying own hardware). The DevOps teams using that Landing Zone have a choice of a bare RedHat Linux 8 server, a bare RedHat Linux 9 server, and a Tomcat (on top of Linux) server.

The design library demo also contains the VMWare design, as LZ2 runs on VMware. And there is a VMware GUI which has to be installed — in this hypothetical example — on Linux, creating a circular dependency.

And finally, you see the ‘enterprise policy tree’. Here we can put policies (a.k.a. enterprise design decisions) that are independent of specific solutions. E.g. we might also have a Landing Zone 3 which contains specials, also as RedHat Linux systems. We might have generic requirements for those RHEL Linux systems too (like al RHEL severs use the same repository) which can be inherited by the actual designs of the actual solutions.

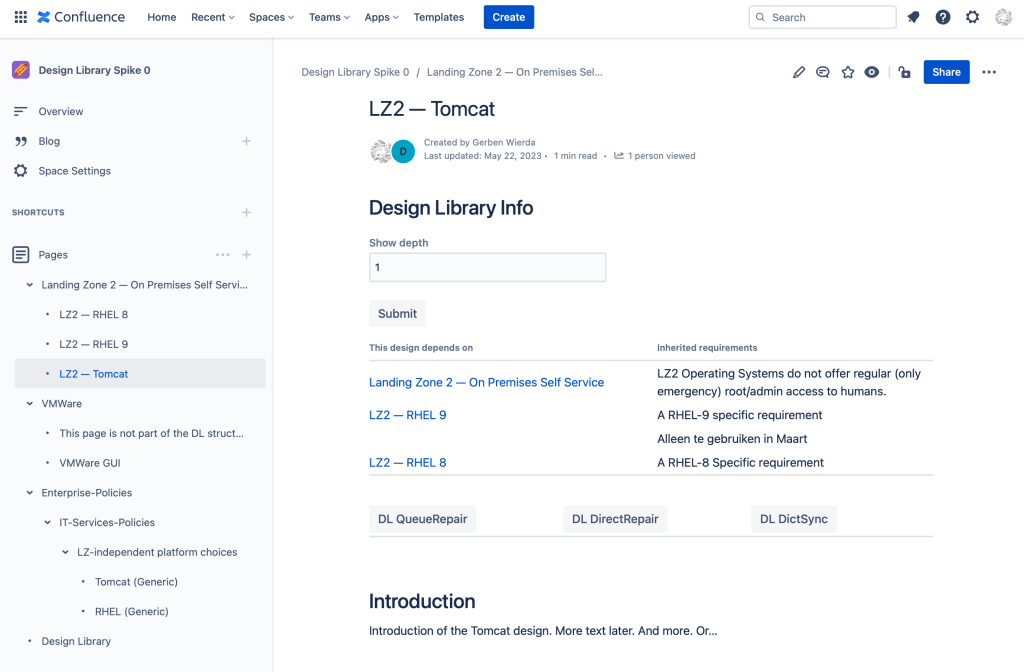

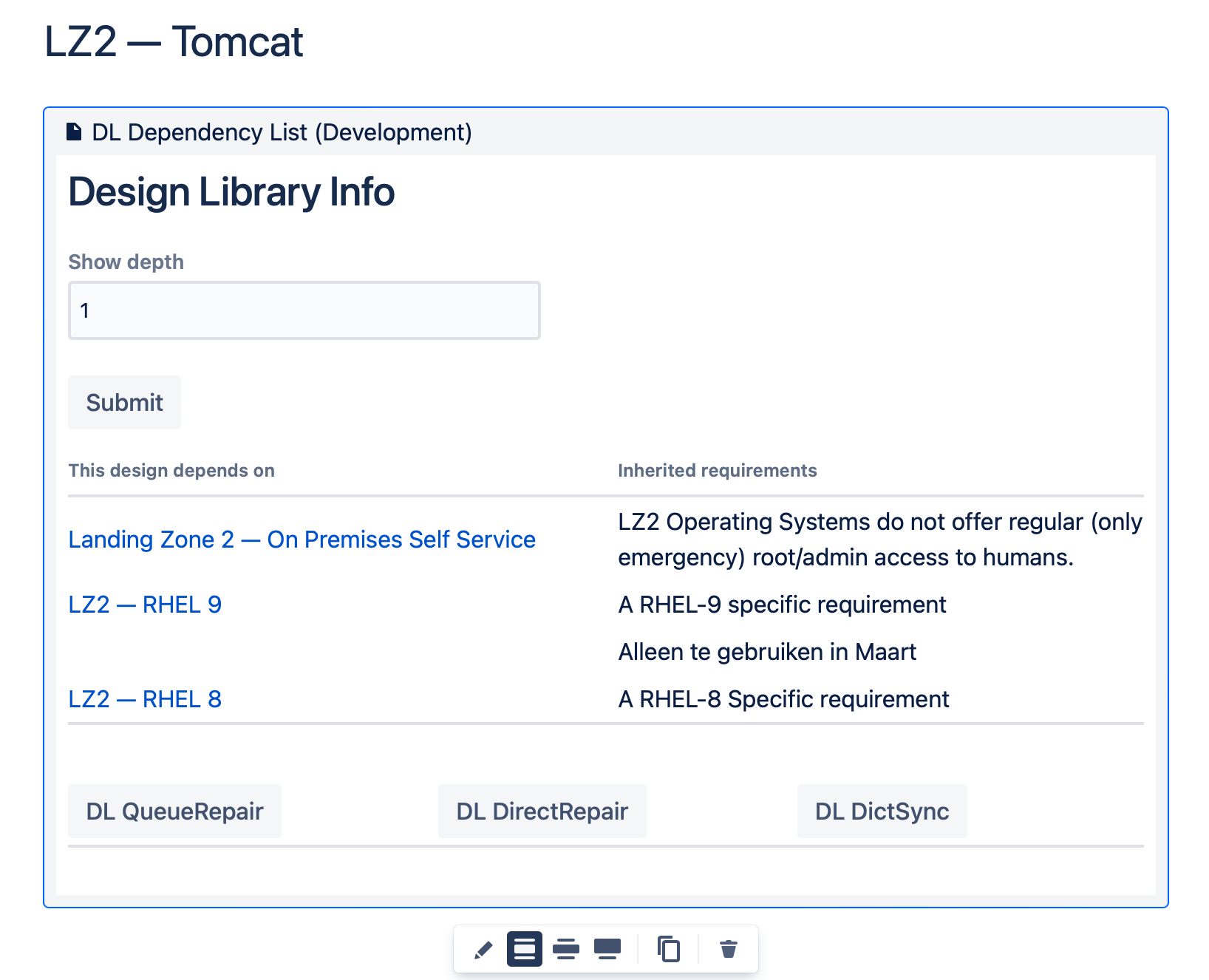

Let’s zoom in on a sigle design: the Tomcat design:

At the top (but it could be anywhere on the page) there is an element provided by my plugin that handles the dependencies. You see here three dependencies:

- The dependency on LZ2, which follows from the fact that it is the parent in the tree;

- Dependencies on LZ2 — RHEL 8 and LZ2 — RHEL 9, which must have been set explicitly.

The right hand side of the table shows the — silly, demo — inherited requirements from those dependencies.

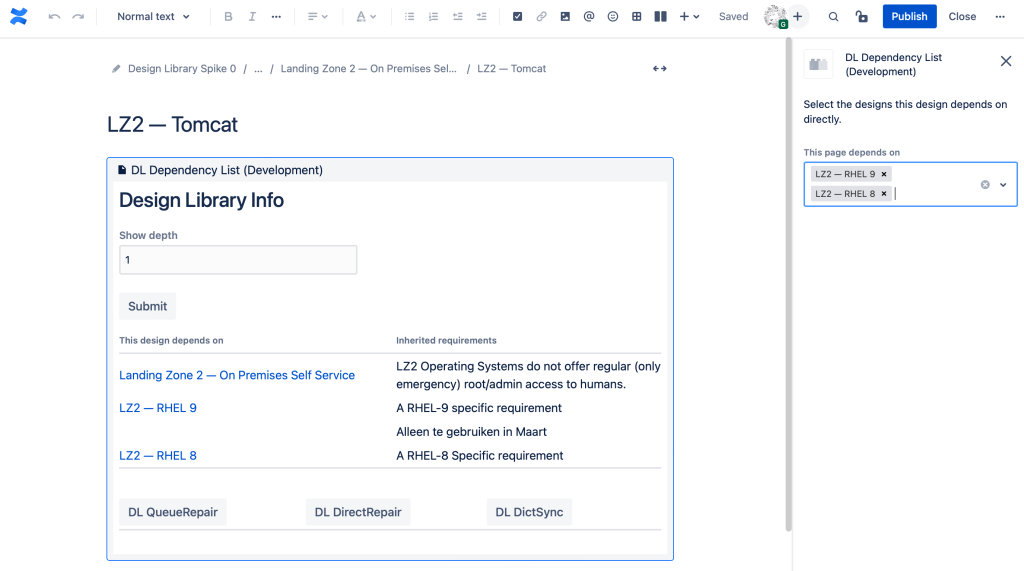

How our Tomcat design has been explicitly linked to the RHEL designs can be seen if we edit the page and then edit the element in the page:

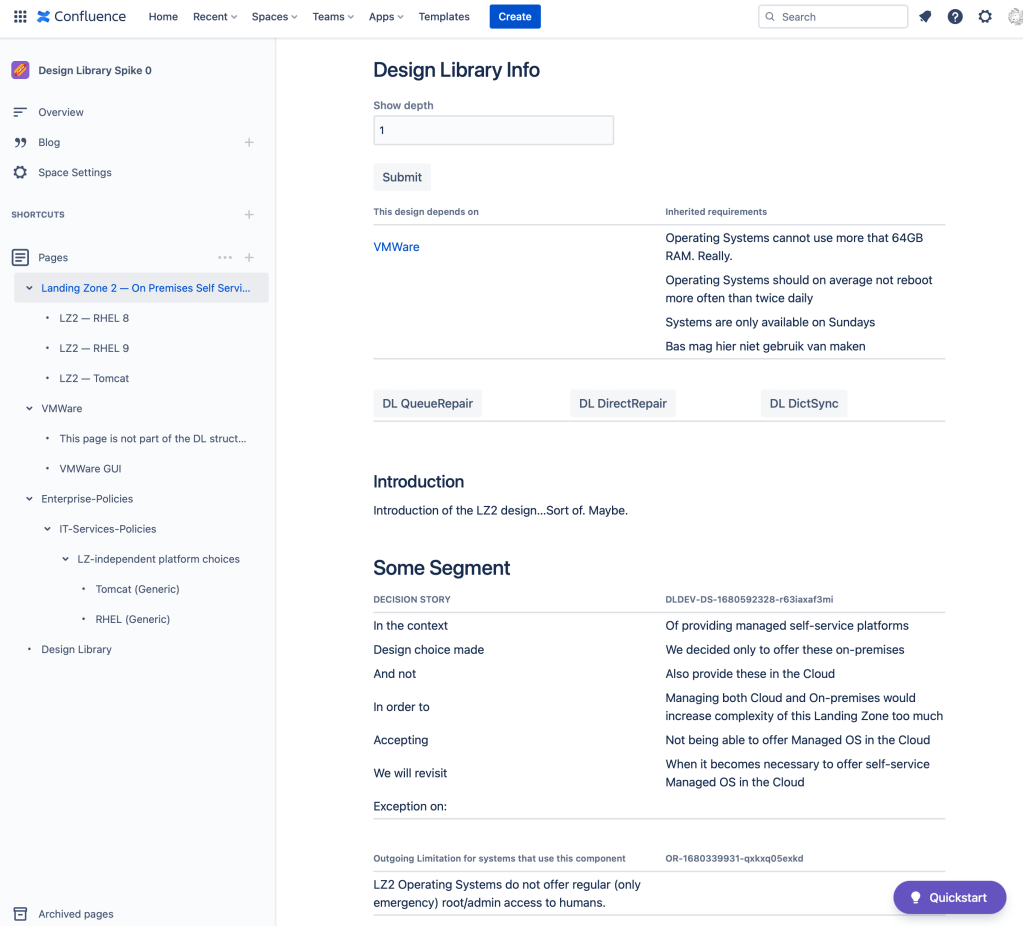

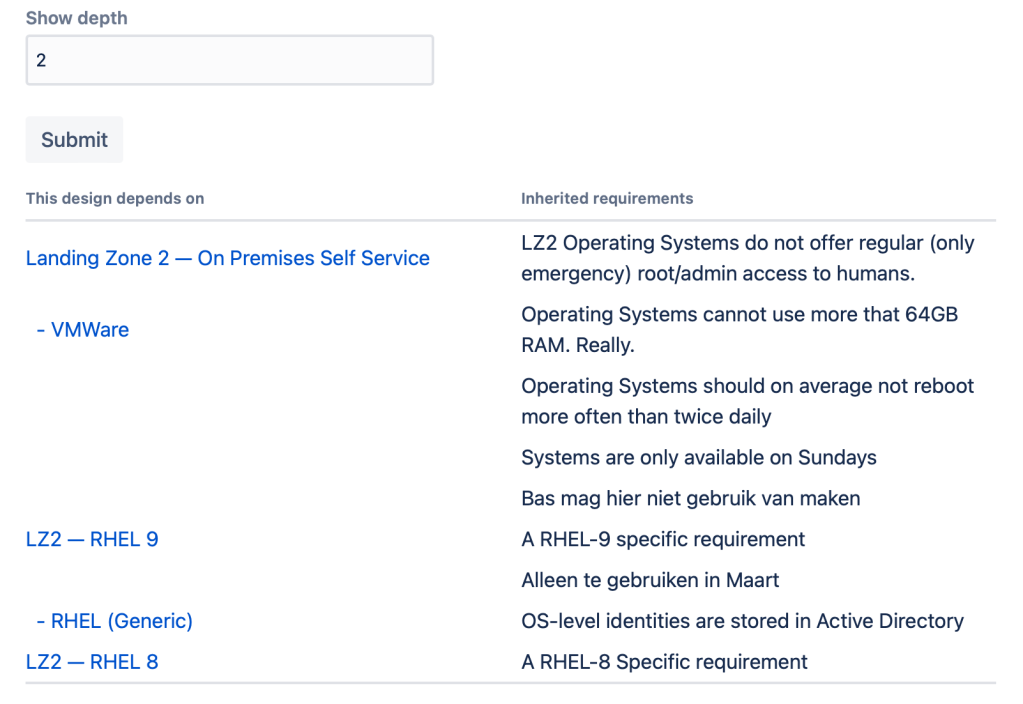

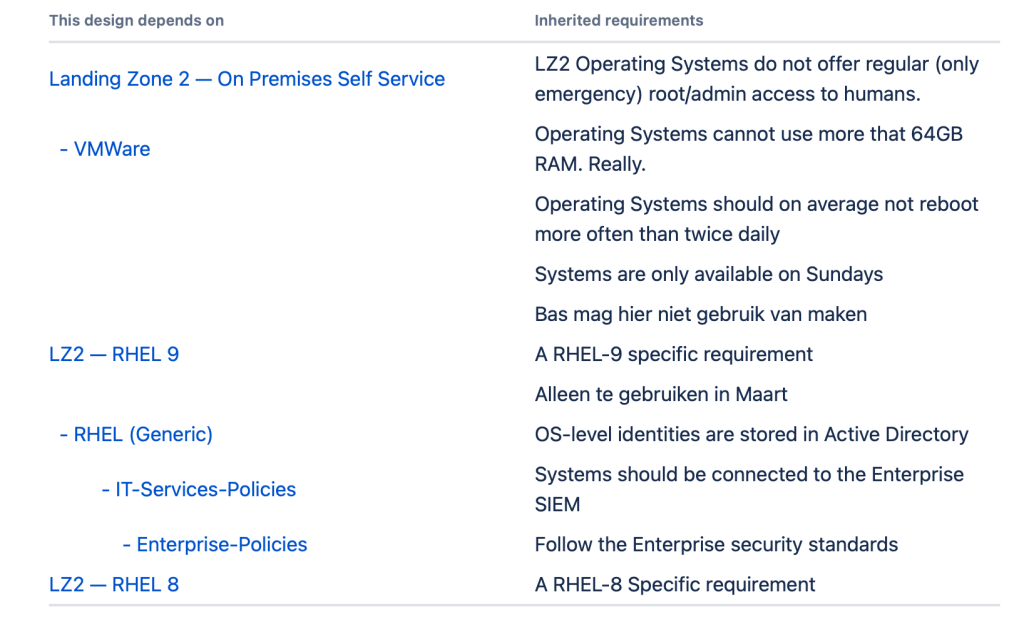

We can of course click and drill down, so let’s click on the generic LZ2 design in our dependency table. There we see that LZ2 itself depends on the VMware design as the systems of LZ2 run in that VMware environment:

And here we see that 64GB max RAM requirement as the initially mentioned example. We should of course like to see this in our Tomcat design as well. And we can over there, by increasing the depth of what we see in the Tomcat design from 1 to 2:

Let’s show all dependencies and incoming requirements by setting the depth to ‘infinite’:

As you can see, nothing is mentioned more than once, even if it can be reached by different routes. And you don’t have to display them all.

Can this become reality?

I think it might, but it will need additional work. Here is a list of things that have to be considered:

- In a landscape of hundreds of designs the full list of dependencies will be unwieldy if not unusable, especially if all policy items become independent outgoing requirements. While fundamentally unsolvable (as it simply reflects reality), we might be able to do something about it, with clever data/UX design, e.g.:

- Every design should probably be able to mark any incoming requirement as ‘not applicable’ once and it should remain hidden afterwards and not passed on;

- Some incoming requirements should be marked ‘do not pass on to dependents’. E.g. some incoming requirement for operating systems might not have any effect for platforms and applications that are deployed on them. These two options can be combined;

- Formal Version management. Designs should be marked when they become a new formal version. From that moment on, dependent designs should be marked as ‘require attention’ and they either should be updated themselves. There is quite a bit of UX design that needs to be thought of here, especially regarding the process of keeping the network of designs up to date on the one hand, while accepting that some designs may be unable to ‘follow’ downstream updates so many versions will be in the landscape (which simply reflects reality). We might also support ‘minor updates’ which follow a different regime (update forced on dependents, owner of dependent design notified but doesn’t need to do anything).

- Life Cycle Management. Implement support for Sunshine LCM‘s ‘start of sunrise’, ‘start of sunshine’. ‘start of sunset’, ‘end of sunset;

- I have looked around for Wiki implementations that allow for plugin development and deployment and as far as I can see, only Confluence can support this, but Atlassian products come with their own challenges, not the least of which is that it seems that the Atlassian ecosystem is a mix of partly finished and partly deprecated incompatible architectures that might superficially look the same, but under water are not. You really learn about a system when you try to program for it, and I must say that Atlassian really can use a good architect and a disciplined program (and investment) to get out of the architectural mess they seem to be in.

If someone is interested to turn this into a (free, open source?) production quality plugin for both Confluence Cloud and Confluence Datacenter, contact me.

Some Final Remarks

Requirements and policies often are design decisions themselves, e.g. at the level of the enterprise. And while we tend to think of requirements as ‘incoming’ elements for our design choices, they have to come from somewhere. That ‘somewhere’ is often another design. They are not just ‘incoming’ they are also ‘outgoing’.

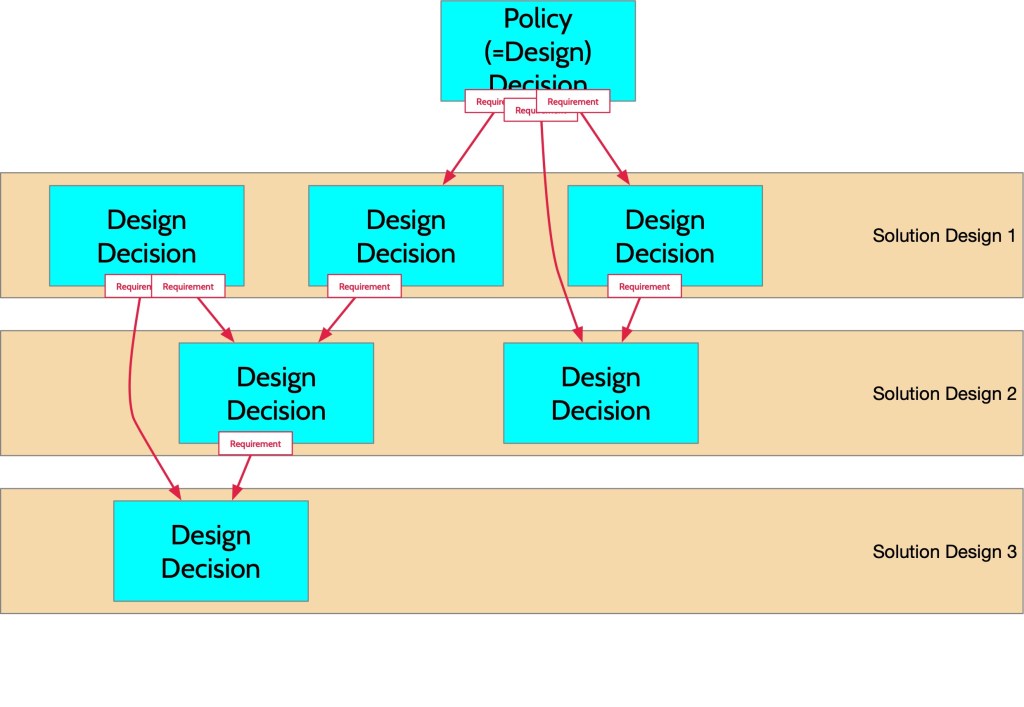

If you think about it, we do not only have a landscape that is a network of systems, but we also have a design landscape that is a network of decisions, some of which create requirements that are linked to other decisions. You might actually look at the solution design as nothing more than a convenient way to group decisions surrounding a single ‘solution’, the boundary of which is if you look closely, never that clear or hard. In a very simplified (and — because of the layering — misleading) picture:

[You do not have my permission to use any content on this site for training a Generative AI (or any comparable use), unless you can guarantee your system never misrepresents my content and provides a proper reference (URL) to the original in its output. If you want to use it in any other way, you need my explicit permission]

1 comment